If It Seems Like Allergies Are Getting Worse for All of Us, It’s Because They Are. This is the New Thinking on Why—and What to Do About It

If it seems like our allergies are getting worse—hay fever, eczema, asthma, peanut allergies—it’s because they are. An estimated 30 to 40 percent of the world’s population have some form of allergy, according to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

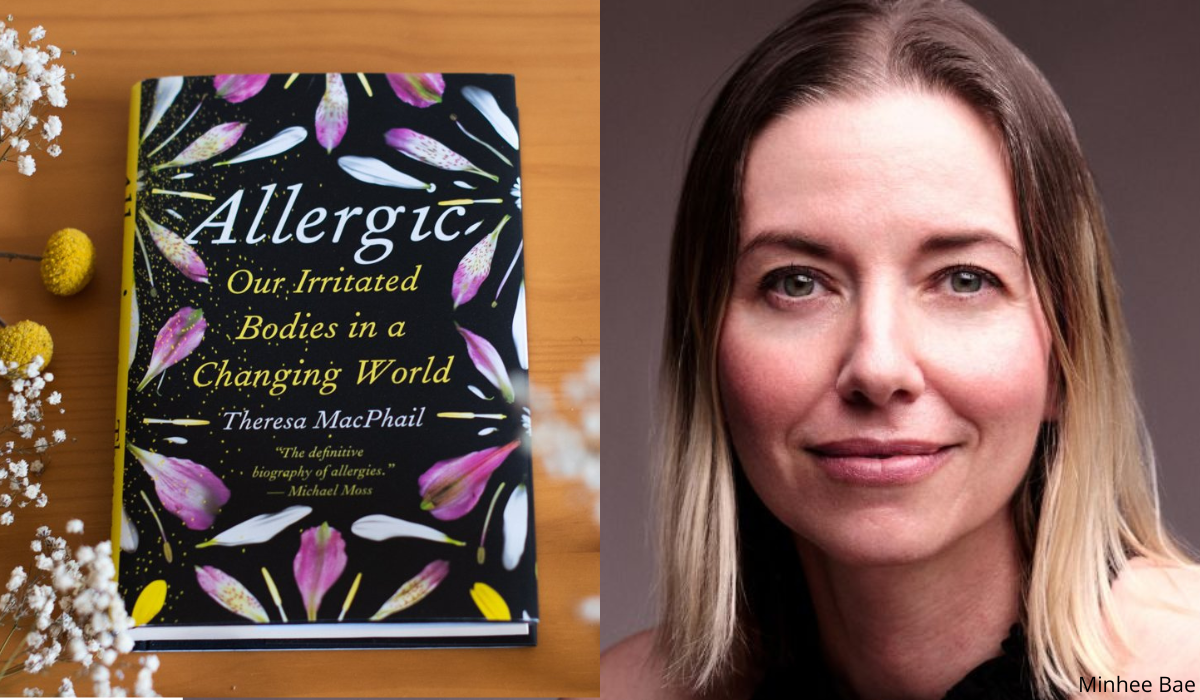

Why? Medical anthropologist (and self-proclaimed science nerd) Theresa MacPhail set out to find the answers.

The topic hits close to home for MacPhail, who is an allergy sufferer herself and whose father died of an allergic reaction to a bee sting. MacPhail meticulously researched what allergies are, why we have them, and what they mean for our future. The result is her new book, Allergic: Our Irritated Bodies in a Changing World, which we sat down to talk to her about this week.

A CONVERSATION WITH THERESA MACPHAIL

At its most basic, what is an allergy—and why do we have allergic reactions?

Basically, an allergy is an immune response.

What happens in an allergic response is that your mast cells—which are immune cells that line everything that touches the outside world and live on your skin, in your intestinal tract, in your nasal cavities—interact with immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies. I like to think of IgE antibodies as the bouncers of the immune system. Their job is to scout anything that the immune cells think are suspicious.

Once you come in contact with something your IgE bouncers don’t like, they alert your mast cells, which then produce histamine. First, it signals to every other cell, Hey, we’ve got an imminent threat. Second, it sends the rest of the cells in the body into alert very quickly, and histamine starts firing everywhere in your body.

Histamine is why we get mucus, and sneeze, and itch. It can constrict the muscles around your lungs. In an asthma attack, for instance, histamine is why people have trouble breathing. It can swell your tissues. And in an anaphylactic attack, it can dilate your blood vessels, crash your blood pressure, and send you into cardiac arrest.

If you’re allergic to something, you might just have mucus. But for someone who has more severe allergic reaction, you’ll see worse symptoms.

What’s behind the rise in food allergies among kids these days?

Well, one of the reasons is that we gave disastrously bad advice to parents for decades, telling them to avoid giving kids anything that was potentially allergenic until they were about 3 years old.

Let’s say you’re a new parent and you make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, which leaves trace amounts of peanut butter protein on your skin. Then, you touch your 3-month-old baby. Maybe some of that peanut protein gets into the baby’s body via her skin, which may be “leaky.” And because your baby’s immune system is still so new, that exposure to peanut protein will prompt an IgE antibody to see it as a perpetrator—and it’ll sensitize her to nuts. So then, when she eats nuts at age 3, her body says, “Nope!” That’s because she’s been primed to see peanuts as not OK.

What we know now is that if you introduce potentially allergic foods in trace amounts earlier than age 3, it essentially trains the immune system, teaching it that a variety of foods are OK, which dramatically lowers the risk of allergy. After age 3, our immune systems are hard to change.

Why are some of us allergic to something (grass or peanuts, for example) and others aren’t?

There are people who are known as atopic, which is when you have a genetic predisposition to higher levels of that antibody IgE. If you're more prone to being allergic to something, you're more primed for those IgE antibodies to have a reaction. This is genetic—but then there are epigenetic as well. If you get the right exposures at the right time, your immune cells learn to tolerate what's around them. We know the immune system is learning the world around it from birth to age 3. So, you’ve got a short amount of time to either stop yourself from developing into an allergic type person—or the reverse.

We’re all hearing that allergies on the rise these days. Why are our allergies getting worse?

One thing people should know is that allergy rates really started to raise here in the U.S. after World War II. The spike isn’t exactly recent. Antibiotic use, processed foods, industrialization and the pollution that causes, people moving from rural areas into more urban settings—all of that has led to more allergies.

Increased antibiotic use, as well as less fiber and more sugar in our diets, are changing the gut microbiome, which is closely tied to the immune system. Pollution is a disaster for the development of asthma and allergic disease. And our move away from rural areas and into more urban settings is known as the hygiene hypothesis or the farmhouse effect: Kids’ immune systems aren’t coming into contact with the bacteria and viruses that are more prevalent in the countryside, which means their immune systems may not be getting the right “training”—which in turn leads to an increased risk of allergies.

In your book, you write about the changes you’ve made to give your body the best shot at avoiding allergies. What are some of them?

I've changed how I think about the bacteria, viruses and fungi living on me and in me. Those trillions of little critters are there to keep me healthy. One theory is that if the balance of bugs in our microbiome is off, it throws off the immune system and makes us more prone to allergies. So, instead of making decisions just for me—my human cells—I think about the decisions I'm making for the non-human cells that are part of me.

I eat differently. I'm not a vegetable fan, but I have made myself like vegetables and I have forced myself to have salads more often. I also try to eat a lot of whole grains and fermented foods, like soy and kefir. I don’t take probiotics. This is a really important point: Probiotics don't work. That’s because there are hundreds of different species in our gut, and we're only starting to understand them. We don't yet know which ones are most helpful for our immune systems. And we don’t know if the strains of bugs in most probiotics are beneficial.

I’m also careful about what I slather on my skin. There are 85,000 chemicals under the toxic Controlled Substances Act here in the U.S.—85,000! That’s so much extra stuff that immune cells can't recognize and don't know what to do with. So I try to put more natural things on my skin and use less of them. I also try to shower every other day to give my natural skin biome a break, and I don't change my sheets as often as I used to. We seed our sheets with bacteria, which stay on our skin and get inhaled (which seeds your nasal microbiome!). So rather than fresh sheets every week, I change them every other week.

What was something that surprised you in your research?

If you look at the funding structure at the National Institutes of Health, something like hay fever only gets $6 million of research funds a year. Meanwhile, aging gets $6 billion. Considering the number of people struggling with allergies, maybe we should shift some of that money to studying the basic mechanisms. Because that research won't just help allergies—it'll help our understanding of autoimmune diseases, and maybe even cancer, considering our immune system is such a big part of why and how cancer develops. We really need to be funding more basic science.

What do you hope readers will take away from Allergic?

I hope that the people who suffer and struggle with allergies feel seen and justified in talking about their allergies. When I was interviewing people, they didn't even know why I wanted to talk to them, because allergies are not taken seriously. These people would say to me, “Well, I don't have cancer. I don't have diabetes.” And it’s like, “Well, yeah, but you don't sleep every night because of your allergies, and you often feel like you can't breathe!”

I hope this book helps those people see they're not alone and that actually, allergies are a much more serious problem than we tend to acknowledge. I want those people to feel better equipped to advocate for themselves.

I also hope people who aren't allergic stop thinking it’s not their problem. Allergies are a community problem. And if we're going to stop this problem, it has to be everyone's problem.

Theresa MacPhail is a medical anthropologist, former journalist, and associate professor of science and technology studies who researches and writes about global health, biomedicine, and disease. She holds PhDs from the University of California, Berkeley and the University of California, San Francisco.