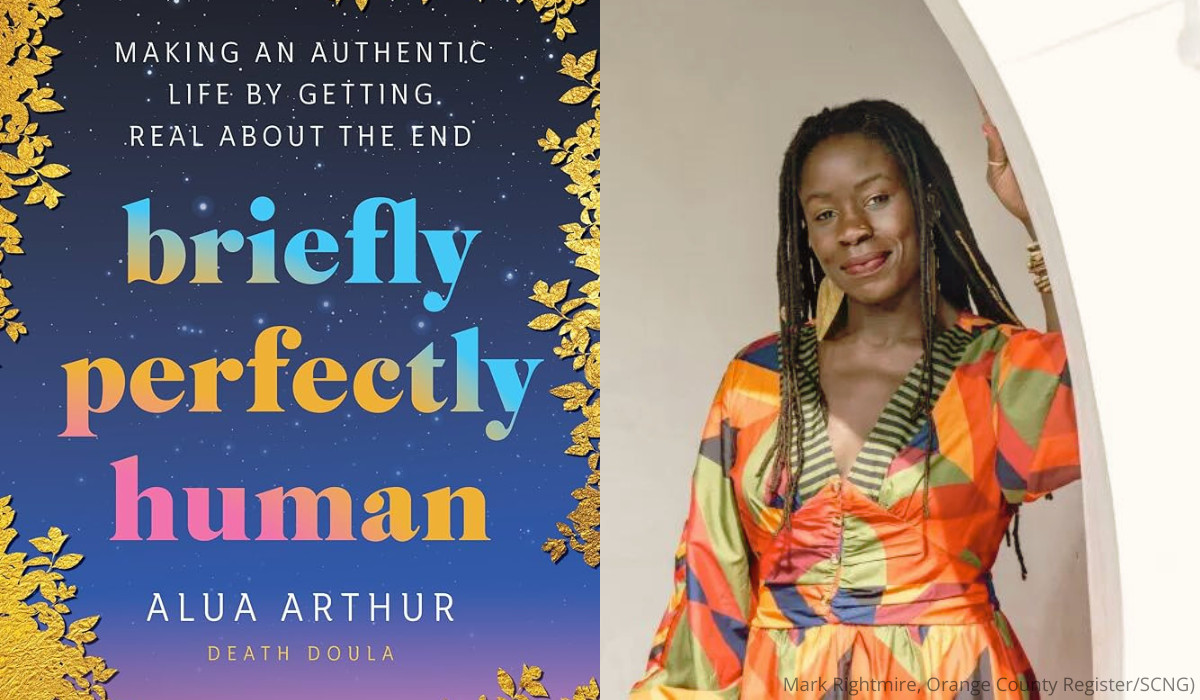

Death Doula Alua Arthur Says to Live Fully Right Now You Have to Get Real About the End. Here’s Where to Start

“What do you think death will be like?”

Alua Arthur posed this question to a new friend she met while traveling through Cuba, a 36-year-old woman who’d just told her she had uterine cancer.

What happened next was a conversation that would change the trajectory of Arthur’s life.

That woman, Jessica, told Arthur it was the first time anyone had asked her questions about the end of her life—most focused instead on hope, healing, and looking on the bright side. For Arthur, it made her wonder: Why don’t we make space for people to talk about the questions that lie heaviest on their hearts?

In the following years, Arthur would learn more about how to make that space. Now, she’s an experienced death doula and author of a stunning new book, Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life By Getting Real About the End. This week, The Sunday Paper sat down with Alua to talk about her work, why thinking about the end of our lives can help us live more fully right now, and so much more.

A CONVERSATION WITH ALUA ARTHUR

Why is becoming more aware of our mortality a great thing to do, no matter how close or far away it may seem?

When I am thinking about my death, I can see very clearly who I want to be, how I want to spend my time, what I want to leave behind, and what I value. My entire life comes into focus when I’m thinking about my death.

When I’m thinking about my mortality, I’m thinking about my whole life. And this allows me to very consciously move in the direction of the things that I want. I also find that people often reach the end wishing that they’d had a different life because they were just kind of floating around. When we can be conscious about our death—when it when we can be aware of it—it allows us to make something of our lives that we feel good about.

We tend to not want to think about or talk about death …

We don’t make space to talk about death at all. That was part of what surprised me about that moment with Jessica on the bus: Everybody was telling her to focus on hope and healing. I’d done that before myself. When people would talk about things that were difficult or messy or hard for them, I would have them look toward the things that were working. But if somebody’s talking about dying, and we don’t give them space for that, we’re invalidating their basic existential questions. Why do we do that?

Why? And how do we start to fix this? How do we help people feel less alone in their grief?

You show up. You tell them that you don’t know how to deal with it, that this is hard for you, and that you don’t know what to say if you don’t. You don’t try to make it better, because how are we going to fix death and pain and grief and loss anyway? There’s nothing that’s going to bring their person back. We can be present for the experience that they are having. We can be present for our own experience. And we can make space for them to be whoever they are. Maybe they want to talk about the Kardashians. Maybe they want to talk about the pain. Maybe they want to talk about their dead loved one, but maybe they don’t. Just let them know that you care. That’s plenty. It’s more than most people get.

What are some of the most important questions all of us can ask ourselves about our death that can help us live more fully right now?

Oh, there are so many, where do we begin? Start with this: Am I living a life authentic to me? That’s the most important one because I find that so many people reach the end wishing that they had engaged with life differently.

You can also ask: What do I value right now? Then, look at your life to see if it matches the things you value. I think that’s wildly important.

I think it’s important to think about this question, which serves as the mission Statement of our organization, Going With Grace: What must I do to be at peace with myself, so that I may live presently and die gracefully?

Really, any question that gets us feeling the juice of life works. Think about the things that really make us feel juicy about being alive, and lean into those as much as possible. Because so many people reach the end wishing that they had spent more time with the minute things. People don’t wish they’d seen the Mona Lisa; they wish they’d spent more time with their grandkids.

What are some of the ways you gut-check yourself to make sure you’re living authentically?

Things that are a full body yes are an easy way to know I’m living authentically.

Like, you put on the outfit and you twirl? Wear it! Even if you think you’re overdressed. Even if you think it looks ridiculous or it’s not appropriate for the occasion. Just wear it. That’s a silly example. But it’s a way to do that gut check for the yes.

How much are kids capable of understanding death? And why is it important to talk about death honestly with them?

They’re capable of understanding a lot more than we think. If we pay attention to the things that they’re experiencing in their world—I mean, Bambi dies, the Lion King. Death is in their faces. In fact, we’re making it for them. And yet, when grandma dies, we say she went to sleep without giving them any context of what we mean. And then you have a 7-year-old who’s afraid to go to sleep because he’s afraid he may disappear and never come back.

I think it’s important that we tell kids the truth. I think it’s important that we also couch it in age-appropriate terms, and we forge as much safety as possible. If a child asks you, “Are you going to die too?” You might respond, “I don’t plan on dying for a long time.” That is my truth. The answer is, Yes, of course, I’ll die. But I’m not going to say that to a 4-year-old.

So, tell kids the truth, couch it in age-appropriate language, and don’t use euphemisms and tell them tall tales about what happens when we die. Because that is how we carry on language and frameworks that are not helpful.

If someone reading this is dealing with the many emotions that come up when faced with witnessing someone who’s dying, what is your advice for how to hold all of it?

Grace, grace, always grace, more grace. This is a tough time. The way you’re doing it is likely the best way, because it’s what you are capable of doing.

Also, take care of your body. Hydrate. Eat to the extent that you can feel comfortable. Speak up for your needs. And allow other people to support you when you can.

What are some of the things all of us should be thinking about to prepare for death?

For starters, Advanced Directives are really important. Being in communication about your health care decision making—who you want to make it, what you want done, how far you want it to go—when you are still healthy is a great place to begin. Also, be in conversation with people who would make the decisions the way that you would and who can hold the conversation with you. Because if you choose somebody who’s like, I don’t want to talk about it, you’re never going to get through.

I think it’s also important that we all spend some time on our fears of death and dying, because it’s often those that underwrite the decisions to do everything at all costs, which means a lot of people end up dying in hospitals or in the medical care system when they’d much prefer to die at home.

You also talk openly about how important it is to think about getting your affairs in order as an act of love to the people who love you. How should we think about this?

There are a few major areas to consider:

Your body and services: What you want done with your body afterward? What services do you want, if anything at all?

Your possessions: A lot of people know that you should get a will or a trust and yes, absolutely. Even if you have a small estate, it’s still important. But also, consider your sentimental items and what you want done with them. I’ve seen families go to war over grandpa’s watch that cost nothing but was something he wore every single day.

Consider dependents: The appropriate place to name a guardian for a child is in a will, but any additional information will be instructive. Children, disabled adults that are under your care, and even your pets. People always forget to name a guardian for your pet, but that’s important, too.

Information and documents: Gather marriage certificates, divorce decrees, passports, Veterans Affairs documents, titles, deeds, and leases.

Online accounts: Make a list of all of your accounts, including the passwords!

This is all something a death doula can help you work through. We work with people when they’re healthy to create comprehensive end of life plans for themselves.

What do you want readers to take away from your book?

I want this book to serve as an invitation into their lives. I want people to start thinking, Wow, okay, so this is what I’ve got. This is it. I want people to reconcile their lives for what they’ve become and then make steps in the direction of the things that they actually want, if there’s still time to do that.

I also want people to give themselves a lot of grace for being human. We give ourselves such a hard time. But this joint is not easy, and a lot of people are doing the absolute best that they can. Your life, no matter how you’ve lived it thus far, is yours.

Alua Arthur is a death doula, recovering attorney, and the founder of Going With Grace, a death doula training and end-of-life planning organization.