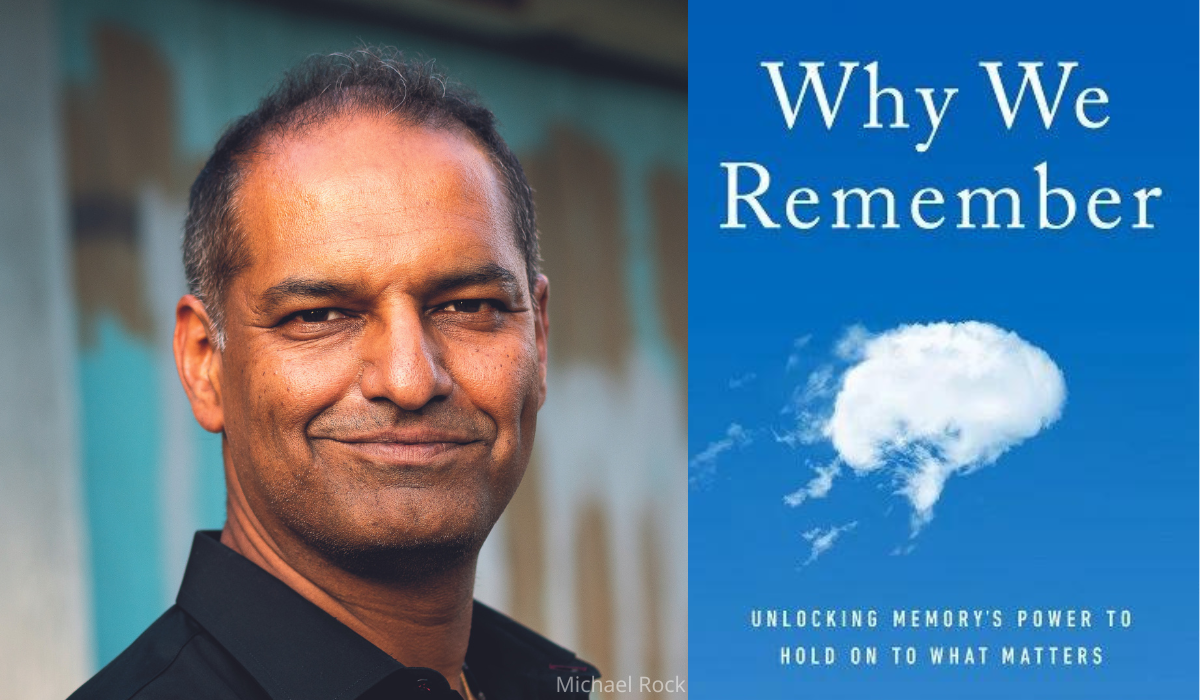

Everyone’s Talking About Memory Right Now. Neuroscientist Charan Ranganath on What We Need to Know—and What We’re All Missing

We expect a lot of our memory. We want it to be absolute and easy. We wish to retain everything and get frustrated when we don't. But this is overlooking how memory works, says Charan Ranganath, PhD. "The human brain is not a memorization machine; it's a thinking machine," writes the cognitive neuroscientist in his new book Why We Remember: Unlocking Memory's Power to Hold on to What Matters. Ranganath, a leading memory researcher, reveals how memory works (spoiler: we're not built to remember everything) and how it shapes who we are.

Ranganath's work is compelling, as it tells us much about how we remember as it does how we move through this world. It also sheds light on a current issue in our society: the criticism of people's memory. We spoke to Ranganath about this, as well as what we overlook when it comes to our remembering selves and how we can, as he says, not remember more but better.

A CONVERSATION WITH CHARAN RANGANATH, PhD

How does our memory shape our lives?

In so many ways. I'll give you one example. You're sitting in a hotel room, and you just woke up in the middle of the night. Your first thought is, where am I? And you have to figure that out. If you have any memory, you think I took a bus in from the airport, I checked into my hotel, and here I am in Austin, Texas. So that memory situates you in space and time. Without that, you could just as easily be in a prison cell. You would not know where you are; you're floating in space and time. So just that alone, the most minimal sense of where you are and what year it is, all grounds you. Imagine if you didn't have that ability. Your present is all there is, and you have no milestones for which to reference it. Likewise, when you're maintaining conversation: You're going back and referencing things that happened previously to make sense of what happens now.

There are bigger examples that include what big decisions to make. Are you ready to marry this person? When do you quit your job if you've had too much of this? These kinds of things are the big decisions that are, I would argue, far more driven by memory than what's in front of you now. And so even though the present is the present, it's the only thing that exists, but we live in this world of memory and imagination, which is how we understand the present.

It's easy to take our memory for granted and be hard on ourselves. We want to remember everything perfectly; if we don't, we think we have a problem. But your work illuminates that fact memory doesn't work that way. What expectations and misconceptions around memory should we release?

Where we get stuck is if we expect memory to be a comprehensive, perfect replay of the past. The reason I think that's counterproductive is, first, it is impossible. I don't know if anybody studied has had a perfect memory for everything they've ever experienced. People differ in memory, and in many ways, we still don't quite understand, but nobody has a perfect memory. And in fact, most people forget most of what they've experienced within a day afterward. So, right off the bat, we have a cultural expectation that makes no sense.

The next very important thing is this idea of memory as a resource that we can use to understand the present and the future. It's a resource that's extremely valuable if you understand that it's there, how it's being used, and if you allow it to give you more options instead of limiting your options.

You recently wrote an op-ed for The New York Times that touches on the criticism of public figures' memory. It seems people can jump to assess and criticize someone's cognitive fitness. You write, "Memory functions begin to decline in our 30s and continue to fade into old age. However, age in and of itself doesn't indicate the presence of memory deficits that would affect an individual's ability to perform in a demanding leadership role." When showing concern over someone's memory, are we putting our attention in the wrong place?

What bothered and motivated me to write this piece is two factors. One, people were saying the problem is age—for both candidates but especially about Biden after The Special Counsel's report. I felt a lot of that was pushing on stereotypes, expectations, beliefs, and fears about what it means to be older. That in and of itself is problematic.

The other part is that people were talking about [Biden] being an elderly man with a poor memory, and that stuck with me because I started to ask, What's the evidence that he has a poor memory? Many people were colloquially calling it 'memory lapses,' but as a memory researcher, I would argue, is this something I should be concerned about, or shouldn't I be concerned about? When I hear 'an elderly adult with a poor memory,' the first thing I think of is somebody who has a real problem, somebody who can't function because their memory is so bad. I didn't see that in any of the examples.

I want to be clear: I don't know anything about President Biden's health in a detailed sense. I could never be in a position to diagnose him, and this isn't a partisan thing. What [the op-ed] really was about was instead of just asking, Is Biden too old? Does he have a poor memory? We should clarify what we know about this topic and get people to say what they really mean instead of just saying 'we think a jury would have this impression.'

In the op-ed, you distinguish between forgetting and Forgetting with a capital F. What's the difference?

Yes! That's not a technical term, but the reason I said it that way is because, again, we talk about both things as forgetting, but one thing is not necessarily as concerning as the other.

So, for example, there's: I went to the kitchen, and now that I'm here, I'm asking, What did I come here to get? Then I go back to the living room and realize, Oh, that's right, I meant to get this. For me, this happens all the time. That's forgetting with a lowercase f. It's not as though I completely had no memory, which is Forgetting with a capital F. [My memory] is there. I just didn't have it when I needed it in the kitchen. Likewise, when you look at President Biden, and he says the President of Mexico when he should have said the President of Egypt. Now, the question you can ask is: Does he know the difference between Mexico and Egypt? Does he remember that he's ever met the president of Egypt? When you ask that, you get the sense that the issue isn't that his memory is gone.

Suppose somebody were to have a conversation with a very important person in a very significant event and they didn't remember that the event took place. In that case, that's Forgetting with a capital F. That is concerning. But forgetting with a lowercase f is basically saying, 'Oh, what's his name again?' Or, 'What year did that happen?' it's just about not being able to access that memory or those details at the moment that you're looking for them. Don't get me wrong, that's frustrating. But it happens to everybody as they get older.

In the Reduce, Reuse, Recycle chapter of your book, you illuminate that the human brain can only keep a limited amount of information. You also say that it's not about remembering more but rather remembering better. How can we start to remember better?

This is the question. There are many answers, which I include in the book. One key point is to understand what makes something memorable in the first place. Something that a lot of memory researchers follow but maybe isn't obvious to the public is that memories compete with each other. It's different than storing files on the hard drive of my computer, where I can store more and more. In the brain, you have a limited pool of neurons, and they're trying to store multiple memories. So those memories are literally fighting with each other. What that means is to be able to find the memory you want; you want it to stick out and be different.

Imagine this: You're looking at a cluttered desk. It's covered in yellow Post-It notes. One has your bank password on it, and all the others have smaller stuff on them. You'll take forever trying to find the note with your password because there's all this competition. On the other hand, if this note was hot pink or fluorescent green, it would stand out against everything else. So, if the things we want to remember stood out, it'd be easier to find them. That's the goal when you're trying to remember something important: Have it stick out relative to everything else.

The problem is with the things we do repetitively because those memories seem like everything else. The brain is very economical. It looks at quality over quantity. Basically, it will look at everything and say, If this matches everything, why should I store that event because I already have that memory? On the other hand, if I pay attention to my surroundings and notice that there's a smell of coffee in the air and it's colder than usual, the more we have rich sensory details, the more I can focus on place and feelings specific to that moment and then the more that memory will stick out.

We are so flooded these days with emails, texts, and notifications that it seems extra hard to have memories stick out. Is that so?

It will always be a problem with losing keys and so forth. Because yes, unfortunately, we have so many things that are grabbing our attention that it's very hard to focus our attention with intention, meaning it's hard to focus our attention on what we want rather than having other things grab our attention. With texts or emails, we form bad habits. I was just in a meeting, and I couldn't help myself; I was checking my email. It's terrible. These are the things that make us remember badly.

What has studying memory taught you about how to live?

It's still teaching me so much. I am very aware of thinking about life in terms of what do I want to remember? And how do I create a life that's memorable? And it could include bad things that I had no control over; are they going to become interesting stories that I can tell later on?

Going back to the pandemic, I have no memories from that period because it was all one big blur of sitting in the same place, doing the same thing. Contrast that with something that I try to do, which is go to different places. Travel is uncomfortable; it can be difficult, and there's a lot of time wasted. But I crave that novelty. And when I look back on a year, these are things that I remember, and that stick out. I do think you can do something to curate your memories and find opportunities for things that you will remember later.

Likewise, I can ask myself, Is this something that I will remember later on and [letting that inform] if I say yes or no to it. Will I want to look back on this time I'm spending looking at TikTok videos? Probably not.

But you'll remember those four days in Lisbon.

Exactly! Exactly. And even if things go wrong, it's still a memory you can carry with you.

That brings up another point: You say making mistakes is great for our memory.

That's another thing that I've taken from this is. I hate making mistakes. I grew up with this idea that you're supposed to get straight As, and if you're struggling, it means that you're not very smart. And in California, many people try to act like everything's easy. Now, I'm very conscious of the fact that if I'm not feeling some kind of discomfort, I'm not learning. Boredom can be uncomfortable. If I'm seeing a talk that is making me uncomfortable, I see it as a sign that this is something that I wasn't thinking about. It's a new perspective. That's been one of the nice things about my work: these aha moments where I see things that I just didn't see before.

I tell my students that if you're never wrong, you'll never be right because that means you're not really putting yourself out there.

Charan Ranganath is a Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience and director of the Dynamic Memory Lab at UC Davis. For over 25 years, he has studied the mechanisms in the brain that allow us to remember past events. He has been recognized with a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.