I Had Dinner with the Future Pope Leo XIV

In October 2023, I sat in the outdoor garden of a Roman restaurant and, along with a small group of Catholic cardinals, scholars, and journalists, shared a meal with the man who would eventually become Pope Leo XIV.

It wasn't the first time I had met him—that took place a few months earlier when Pope Francis had brought him to Rome to run the powerful Vatican office tasked with vetting potential Catholic bishops around the globe. Bishop Robert Prevost was Chicago-born but he had spent most of his adult life outside the United States, in Italy and Peru.

Now, the pope had called him to Rome and vested him with tremendous responsibility. As an American journalist covering the Vatican, I was thrilled that Pope Francis had chosen an American for such an important position. I hoped that our shared nationalities would give me regular access to him. I wanted to know where he stood on hot button issues, like women's leadership and LGBTQ ministry. And I wanted to learn how the pope had identified this relatively unknown figure who had not been in the church spotlight, to be a critical leader on his team.

Prevost had declined an official interview request—the work of his office was sensitive and he wasn't comfortable going on the record. But, he was willing to get to know me, American-to-American. For about an hour, I sat with him during that first meeting and asked how he had gone from a kid on the southside of Chicago to a missionary in Peru to the head of his religious order, the Augustinians, to now one of the men who Francis would eventually make a cardinal—someone who could eventually become a future pope.

He answered thoughtfully and sincerely, but I could tell he was not someone who sought out the media spotlight. But he was also shrewd. Soon, he put me in the hot seat. He had hardly lived in the United States as an adult and there was a lot about his home country, especially the church in the United States, that he did not understand. He asked me why Americans were the ones often resistant to Pope Francis' efforts to make the Catholic Church more welcoming and inclusive?

We concluded our meeting and agreed to stay in touch. I went on to see him at many of the receptions that take place at Roman embassies and universities where journalists and high-ranking Vatican officials often crossed paths. And when we found ourselves dining al fresco that October evening nearly two years ago, I was struck that around that table of Vatican powerbrokers, Prevost was exactly the same humble man that had welcomed me into office several months prior.

The dinner took place amid a month-long gathering at the Vatican that Pope Francis had convened to discuss some of the most divisive topics in the church: clergy sexual abuse, the need for greater accountability of priests and bishops, the possibility of married clergy, LGBTQ issues, and much more. Some people of the church deemed them too taboo to discuss. Francis thought they deserved attention. The stakes felt incredibly high.

The views at that table that evening were hardly homogenous. As waiters poured chianti and served carbonara, various attendees expressed their own opinions about the proceedings happening in and around the church as its very future was being debated. As a journalist chronicling it all, I felt privileged to be there to get a sense of where the battlelines were being drawn. As a reporter, I didn't weigh in—I sat and listened (and yes, sipped plenty of wine).

Looking back at a friend's photos of that evening, I was struck by images of guests gesticulating as they argued for or against certain positions. Seated two spots down from me was Cardinal Prevost, who is captured in the photos taking in the scene and listening intently.

The dinner eventually concluded and we all went our separate ways. Despite being a cardinal—what have typically been described as “princes of the church”—Prevost got into his small compact car and drove himself home.

Over the following year and a half, I continued to see the cardinal on various occasions, and we traded opinions and insights about various Vatican affairs. Pope Francis—a trailblazing pope who had sought to breathe life into an institution that some feared was on life support—continued to age and decline in health.

When he died on April 21st of this year after a long hospitalization, I was one of the few reporters to suggest that Cardinal Prevost might have a shot at the church's top job. To be clear, it was not a job that he would have wanted. My own interactions with him had cemented in my mind that he was someone happy to keep away from the cameras and work diligently in the background.

But I also knew that because of that, he had earned a reputation as someone who was well-trusted in the Vatican (a place where few people trust each other!) and that those who worked closely with him were quick to attest to the fact that he believes everyone should have a seat at the table and a chance to be heard.

The conventional wisdom was that someone from the United States would never be pope because America has too much power in the world already. But as I argued in the lead-up to the conclave, fellow cardinals did not view Prevost as your typical American. His biography as someone who had spent one-third of his life in Latin American and another third in Europe meant that he had a global vision with broader horizons than most. His own background as a descendant of the Creole people, who moved to Chicago from New Orleans, told a complex and multicultural all-American story. And at a time when some Americans are calling for a withdrawal from the world around us, Prevost's commitment to the common good that extends beyond any one particular country's borders was an attractive credential.

On the evening of May 8th—after just over 24 hours—white smoke appeared from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel, signaling that a new pope had been elected. When Cardinal Robert Prevost appeared on the balcony of St. Peter's Basilica as the newly elected Pope Leo XIV, many of my journalist colleagues were caught off guard. Everyone seemed to be asking the same question: “How had this relatively obscure figure experienced this meteoric rise from missionary priest to now pope of the Catholic Church?”

In the days that followed, I spoke to many of the cardinals who had taken part in the secretive election process known as the conclave. “How did 133 cardinals from more than 70 countries around the globe quickly unite behind this outsider candidate?” I asked them. One cardinal noted that he believed the rapid election of a very diverse group of men could be “something the world could see as a model of how we bridge our differences.”

The scene around the Vatican in those days seemed to echo that sentiment. Hundreds of thousands of people from around the world descended onto Rome to welcome the new pope. They put aside their differences and waved colorful flags representing their own countries and cultures and shared in this fresh optimism of what the new pope represented to the world: that building bridges is still possible.

In my conversations with cardinals, they acknowledged that the election of a new pope was taking place at a time when there were deep divisions in the church but more broadly in the world around it. The loudest voices—be it coming from the halls of power or on bully pulpit of social media—seem interested in talking over the least of those in society. Pope Leo, by contrast, seemed interested in listening first.

Last week at a book talk in Chicago, I met some of the pope's second cousins. Like many of the folks I met in Pope Leo's hometown, they were elated by the news of his election and full of questions: When might he visit the United States as pope? Might his Creole roots motivate him to do more to help the Catholic Church recognize the contributions of Black Catholics? Where does Pope Leo stand on some of the big issues facing the church today?

I offered some tentative predictions about what the Leo papacy might hold and was tempted to wade into the fray with my own hot takes, but also kept in mind my own experiences with the man who would go on to become pope.

I had been impressed with him initially as a man who wielded great power but was eager first to learn and to listen. It offered such a contrast from the world around us, and even in his own church where many seem to want to provide answers without considering if the right questions were being considered. Long before he had been elected, he had given me hope that a different way forward is possible. The best thing we can all do now do for the new pope is to follow his example.

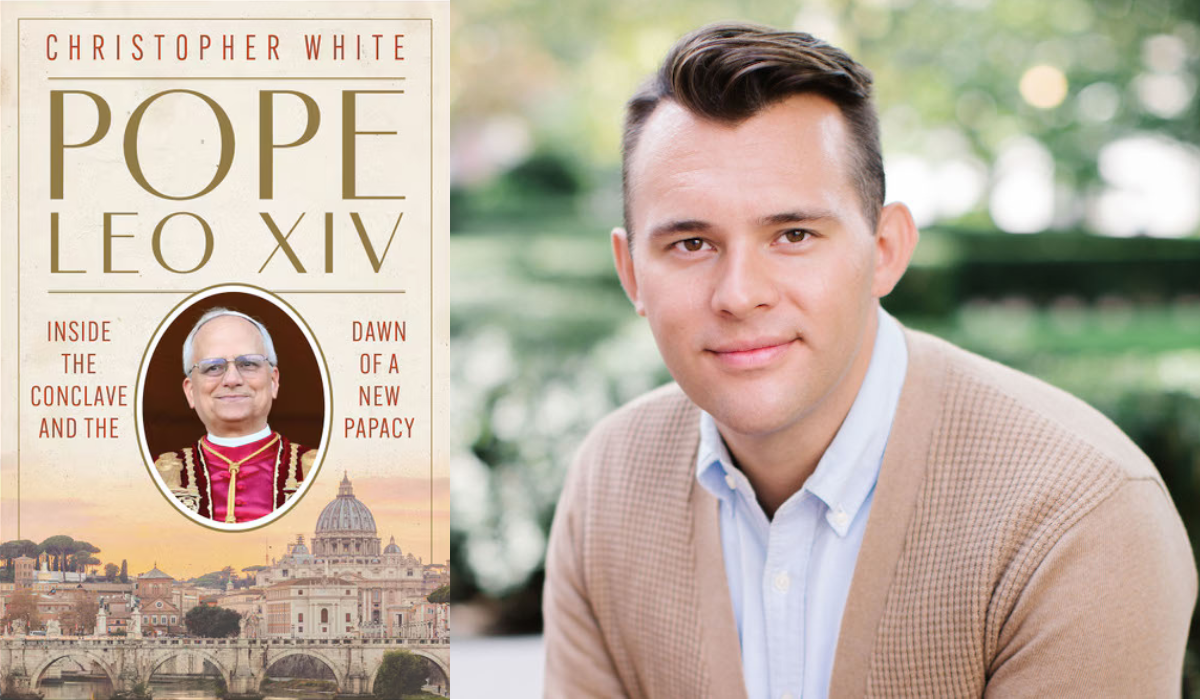

Christopher White is the author of the newly released, “Pope Leo XIV: Inside the Conclave and the Dawn of a New Papacy.” He is a senior fellow at Georgetown University's Initiative for Catholic Social Thought and Public Life.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.