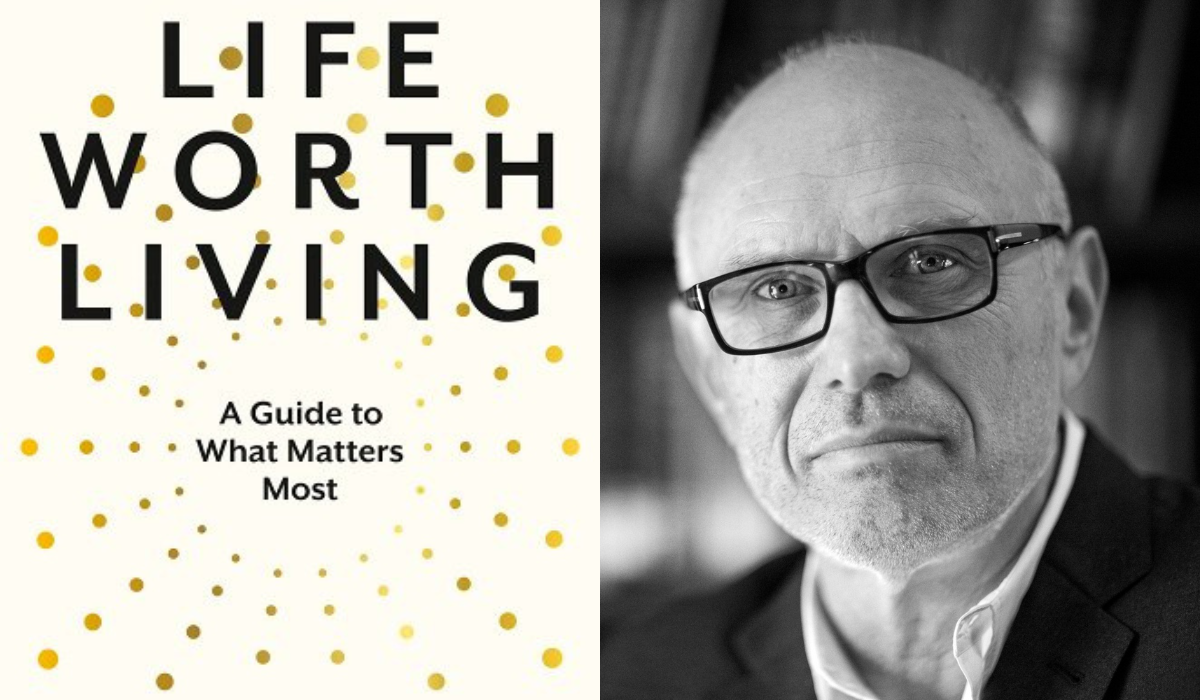

Do You Want to Live a Life Worth Living? Do You Need Help Figuring Out What Matters Most? This Yale Professor Just Wrote the Guide

What does it mean to live a good life? What shape would a life worth living take?

Are you succeeding in the art of living?

For years, Yale undergraduates have been able to ponder these questions in one of the university’s most highly sought-after courses, called Life Worth Living. In class, professors Miroslav Volf, Matthew Croasmun, and Ryan McAnnally-Linz help students consider what makes life meaningful by exploring a number of founding figures and texts of diverse traditions—from the Buddha and the Torah to Jesus of Nazareth, Muhammad, and Nietzsche.

Now, these professors are giving all of us a framework to think about these pressing questions in their new book, Life Worth Living: A Guide to What Matters Most.

The Sunday Paper sat down with Volf to talk about the book, what he and his co-authors hope readers will take away from it, how he revisits these important topics in his own life, and more.

A CONVERSATION WITH MIROSLAV VOLF

Your book tackles what you call “the Question”—a hard-to-articulate query with countless ways to ask it: What matters most? What is a good life? What is the shape of a flourishing life? Why isn’t the Question clearly defined?

It’s an ancient question, really. People have asked it in great religious traditions for centuries, even millennia. In different settings, the question is expressed in different ways. Notwithstanding all these differences, there’s a kind of heart to this question, which I have expressed in this way: What kind of life is worthy of our humanity? What kind of life honors what we are as human beings?

That seems to me to be a fundamental question. And yet it is a question that we very rarely ask these days. For centuries, our great universities had this question at the center of their curriculum. Then, in the 1970s, that question gradually became pushed to the margins. That’s what triggered me to teach the class, Life Worth Living, with my colleagues at Yale. It’s this weight of the question contrasted by rarity by which it’s being asked that generated the need for that class and ultimately this book.

The introduction to Life Worth Living is titled, “This book might wreck your life.” Why does asking some version of the Question threaten to change life as we know it?

We sleepwalk through life in many ways. We follow our dreams, but we’re not sure why we have those dreams. Once you step back and start thinking about your life—What is significant? What is worthy of your humanity?—you might suddenly find yourself arrested in the trajectory you were taking and ask yourself, What am I doing with my life?

Sometimes the Question startles us, it “wrecks” a life that is unworthy of us and sets us on a better course. Sometimes it may be that we experience a wreck in life, and that wreck alerts us to a redirection.

What are some of the ways you personally revisit the Question, even when life gets busy?

I’m a religious person. I regularly attend church services, and that ends up being a regular way to touch base with where I am.

I have also made it a habit to revisit the Question on a weekly basis; I meet with a group of friends, and we read biblical texts. There are also a variety of ways on a daily basis where I might have a conversation that will stimulate me to think about the Question. The Question is always with me, in the background. My mother influenced my life tremendously, and she did this. She paid daily attention to what was happening to her interior life, and how she could live the life she felt she was called to live despite the pressures that existed around her.

What is your best advice for people reading this who think, That sounds nice! I’d like to have a daily or weekly practice that inspires me to revisit the Question?

Well, you have already done the first step: the question intrigued you. The second is to recognize that it’s important to you—that it matters to you deeply for the simple reason that you and your life matter. The Question has to matter, because it requires us to attend to it regularly.

I would also say this: Find the classical texts, depending on what tradition you come from, and spend a little bit of time reading them. It’s also important to have friends to do this with. It’s very hard to first establish the habits that will inspire you to revisit the Question, and then to keep them. Being responsible to a group of friends ends up making it possible. Perhaps I should also say: Start with our book, read it slowly; it will guide you.

Tackling the Question in a university setting, where you’re surrounded by peers thinking about the same big topics, sounds incredible. Any advice on how to talk about these big topics with friends without scaring them off?

Some people might be scared off—it might be too much for them. But in private conversations, as well as in lectures, I find people are quite receptive. Once one considers this Question about how worthy our lives are and how little attention we pay to how we live them, we can have a greater sense of the meaning in life. People respond to that. I’d be surprised if readers of The Sunday Paper wouldn’t find a few people in their lives who would say, “Oh, I’d like to explore these questions with you.” I’d encourage you to simply bring it up, see who wants to talk about it. It shouldn’t consume your life; it should accompany it.

Your book aims to bring the concepts you teach students who take your Life Worth Living class at Yale to the rest of us. What are some of the most important concepts you hope readers will walk away with?

A key early chapter in the book is the one on responsibility. It asks: To whom are you responsible for your life? I think it’s important to step back and actually ask that question rather than live without the sense of to whom you’re answerable.

There’s another important question I hope readers will really think about: What is the shape my life should take? We break it down into three components:

1. How should a good life—a flourishing life—feel? Reflect on what kind of emotions are appropriate, and how one comes to have those emotions.

2. What kind of circumstances do I require to live life as I imagine it? Why do I require those circumstances? This covers things like housing, looks, reputation, and so forth.

3. How should I lead my life? How should I act in the world? This isn’t simply what you feel like doing, but rather about what you believe you should do.

Once you attend to these questions, you’ll have covered quite a bit of your life. These are good beginning steps to living a life that is truly worthy of our humanity.

What does it mean to you to live a life worth living? Has your answer changed over the years?

It’s a tough question to summarize quickly. So, let me try to answer in terms of some of the concepts we’ve already talked about.

If I asked myself, to whom am I responsible? The answer is twofold: One, I’m a theologian, a Christian, and I feel responsible to God. God, who is unconditional love who created me, requires me to live a certain kind of life to find my own fulfillment. Two, I have a 5-year-old daughter, and I feel I’m responsible not just for her and to her. I feel she needs to grow up with a sense that she has a father whom she could admire, one whom she will think is worthy of her respect. In that sense, she has a claim upon my life, and I’m responsible to her for that.

In terms of my emotions, I think that in many ways, the most appropriate emotions are the ones that keep us in touch with how the world really is. I’ll put it this way, quoting from the New Testament: “Mourn with those who mourn, and rejoice with those who rejoice.” That covers the range of emotions in which we are attuned to what is happening to us and attend to the good or bad experiences of others as well as our own.

In terms of my agency, I feel that I should love my neighbor as I love myself. Now, that’s a very tall order. The question is: Who is my neighbor? But it seems clear that the good life requires that I am concerned for more than just myself; it requires that I go out of myself. I receive a sense of the meaning in life—of the importance and weight of life—as I give myself to others while living my own life.

In terms of what circumstances I require to live life that is worthy of my humanity? Lately, I try to think about how to set limits, given the world in which we live. We are never-enough people living in a never-enough world. For me, that’s central in terms of my circumstances. I want to find the limits and be joyful in those limits. Not because I don’t want to drive a nice car or eat really great food. Rather, because there are other ways in which I can use resources than simply to benefit myself. We live in a world of great discrepancies in power and wealth—a world in which our standard of living is paid at the expense of our natural environment. I think these things call on us to limit ourselves, and to find contentment within the limits that we can responsibly have.

One of my favorite lines of any literature comes from Dante’s The Divine Comedy, Paradiso. There are levels of achievement in Dante’s paradise. There are souls on the lowest rung in the hierarchy of heaven. And the question emerges: Well, how can you be satisfied to be there, on the lowest rung? How can that be heaven for you? And then comes the response from those souls on the lowest rung: “We long for what we have.”

Normally, we long for what we don’t have. But actually, the spirit of enjoyment is to long for what we already have.

I mentioned I have a young daughter. I have her and I long to have her. If I stopped longing for her, the relationship would die, become a shell. That longing vivifies the relationship. The same holds true for anything that we have. Obviously, many people don’t have enough. I’m not suggesting the only thing we should do is long for what we have; there’s a proper place to long for more or other things than what we have. In the Jewish tradition, there’s a celebration of the Sabbath—the day we don’t work, when we celebrate the good that is rather than striving to achieve the good we don’t yet have. Maybe there’s something here for all of us. Six days of the week—20 hours a day, 50 minutes an hour—we can be discontented, but one day—or 4 hours each day, 10 minutes each hour—we should celebrate, longing for what we have.

Are there any moments that stand out for you as particularly special or noteworthy when students have told you how your Life Worth Living class impacted them?

I’ll never forget what one student said: “This class gave me, for the first time in my life, permission to think and grapple with intellectual seriousness about the question of what makes my life worth living.” Before taking the seminar, she thought intellectual work, study, and attention should be devoted to solving economic, political, social problems—not this Question of what makes life worth living. She was transformed when she realized this is the Question people have thought very carefully and deeply about for centuries.

The book is a guide to help all of us think through the Question. It’s a very big Question, and we break it down and introduce readers to some of the conversations going on about it over the centuries.

Miroslav Volf, Matthew Croasmun, and Ryan McAnnally-Linz teach the most in-demand course in Yale College's Humanities Program: Life Worth Living. Students describe the course as life changing, and preliminary analyses by an outside researcher show strongly significant effects of the course on students' sense of meaning in life.Volf is the Henry B. Wright Professor of Theology at Yale Divinity School and director of the Yale Center for Faith & Culture, and was awarded the 2002 Grawemeyer Award in Religion for Exclusion and Embrace, which was named one of the one hundred most influential religious books of the twentieth century.

Question from the Editor: What are some of the ways you are living a life worthy of humanity?

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.