Autoimmune Disease Is an Epidemic. Dr. Sara Szal Gottfried Says THIS Is the Surprising Trigger Nobody Is Talking About

In her precision medicine practice, Sara Szal Gottfried, MD, is always on the hunt for patterns—and in recent years, she discovered an eye-opening one: Many of her patients with autoimmune disease have a history of trauma.

Dr. Szal Gottfried’s finding is backed up by research, which shows that up to 80 percent of people with autoimmune conditions (which happen when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own healthy tissue and cells) experienced significant emotional distress before getting sick.

Now, the Harvard-trained physician is on a mission to help the tens of millions of people who suffer from these conditions—as well as those without a diagnosis who are at greater risk than they realize.

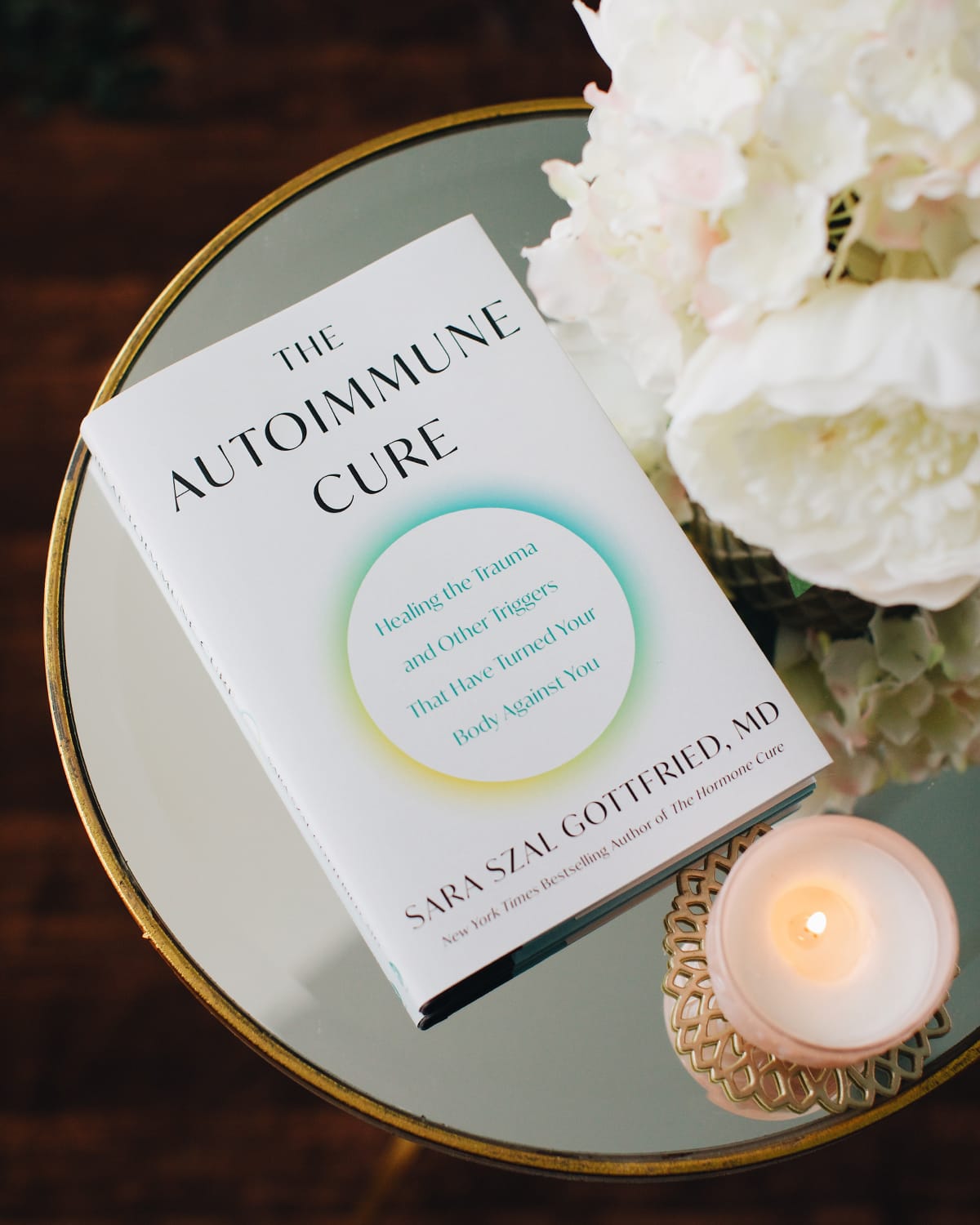

This week, The Sunday Paper sat down with Dr. Szal Gottfried to talk about her new book, The Autoimmune Cure: Healing the Trauma and Other Triggers That Have Turned Your Body Against You, and what she wants everyone to know to break the vicious cycle of autoimmune disease.

A CONVERSATION WITH SARA SZAL GOTTFRIED, MD

We keep hearing that autoimmune disease is on the rise. What prompted you to look at autoimmunity for your new book?

There was a confluence of things that inspired me to really look at autoimmunity. One was the pandemic, which exponentially increased the number of people with autoimmune conditions. In fact, long COVID is thought to be an autoimmune condition.

I also did some testing about six years ago and found that I have anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), which means I make antibodies against the nucleus of the cells of my body. [ANAs are possible signs of autoimmune diseases.] I was shocked to find that my ANA level wasn’t just a little bit elevated, it was hugely elevated. Whenever things like that happen, I don't see them as happening to me, I see them as happening for me, and so it kicked off my curiosity.

I started talking to some colleagues about this. Mark Hyman, MD, just launched a new laboratory test and he's had 100,000 mostly healthy people take the test so far. He's found that 30 percent of these 100,000 people are positive for anti-nuclear antibodies—and 13 percent of this group has antibodies against their thyroid. Nearly one in three people are struggling with autoimmunity—and most don't know it. So, we’re seeing this dramatic rise in autoimmunity. But then, of course, the question is why? And why is it that four out of five people who have autoimmunity are female?

You write that autoimmune disease is a perfect storm of three factors: genetic susceptibility, increased intestinal permeability, and a trigger. And the big idea of your new book is that trauma is often a trigger. How’d you come to this conclusion?

I would broaden the trigger to include perimenopause and menopause, because I definitely saw that in my practice—and I think a lot of The Sunday Paper readers can relate to the dysregulation of perimenopause and menopause.

Many of my patients who suffer from autoimmune disease have a history of trauma. Emerging research shows that up to 80 percent of patients with autoimmune disease experienced significant emotional distress before getting sick.

Most of us have experienced trauma at some point. We live in a world where we're watching graphic violence, we've got this exponential rise in gun violence, we're seeing climate violence. We are living with a huge amount of trauma. I think that that's one factor.

Our immune system requires a sense of balance—a sense of homeostasis. Homeostasis is this idea that you've got an internal system of checks and balances that keep you in equanimity, regardless of what's happening externally. Trauma disrupts that homeostasis. And, depending on your body, this has different consequences.

For some people, they'll have psychological results; they'll develop Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, disordered eating, or attention deficit. Some people will experience hormone changes, such as chronic cortisol issues. And then some of us have immune issues—that's where our vulnerability is.

When it comes to women and autoimmune disease, what do we know about why women disproportionately suffer?

I often joke that it’s a health hazard to be female in this culture. But it’s actually not a joke when you consider the disproportionate rates of depression, insomnia, Alzheimer’s disease, and autoimmune disease.

There are the biological factors, which are the sex-based factors. And then there are gender-based factors, which are socially constructed.

In terms of biological factors, one is that women go through massive hormonal changes that men don’t go through. Pregnancy, postpartum, perimenopause, menopause—those all increase our vulnerability to autoimmune disease. We've also got more trauma exposure than men. If you look at some of the original studies that were done in the 1990s looking at the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) questionnaire, women had about 10 percent more trauma load compared to men. And then even when you compare men and women who are exposed to the same trauma—say, a military event—women have higher rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). So, we've got a lot of biological vulnerability

Then there are some gender differences too, such as coping with a culture that has a huge pay gap and doesn't value women's work the same way that they value men's work. There are a lot of different factors that conspire to create a greater risk in women.

Unhealthy levels of stress may increase our future risk of autoimmune disease. Why is this? And is it possible to have a healthier stress response in these stress-inducing times?

Yes! I feel like if I can do it with an ACE score of 6, with going through a divorce last year, then pretty much anyone can learn to do this. It is possible to develop a healthier stress response. But what’s important to remember is that you have to recognize it first. A lot of people run around dysregulated and they don't know it.

Having a sense of how much trauma you've experienced is important. What is your ACE score? Have a sense of how much time during the day you spend in a state of relaxation and restoration and doing things that are good for you in the long term. I would not put alcohol in that particular category. I think a lot of the things we reach for to create a sense of relaxation are short-term solutions that ultimately backfire. What is really called for here is a way to work with the body to become more regulated so that we're not as vulnerable as we are in that state of toxic stress.

How do you regulate your stress response and rise above the noise?

I track my stress response with a wearable. Because one of the things about trauma is that you can become functionally dissociated. I think this is especially true for doctors, teachers, nurses, first responders—you just go into kind of a default pattern of respond, respond, respond. A wearable that lets me track my heartrate variability, which is the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, makes a difference for me. I track my daytime stress—looking for when I’m stressed and engaged, which is where I want to be when I’m working, and then when I’m relaxed and want to be restored.

What helps me rise above the noise? Eating foods that are good for my immune system. Addressing leaky gut, because I have a tendency towards it as do most of my patients. Embodiment practices—I do a few forms of somatic therapy, which I think works a lot better than talk therapy. And then these healing states of consciousness, which you can access with holotropic breathwork (which I have in the book) and psychedelic medicine. These are what I find to be most effective.

There's girlfriend medicine as well—spending time with people who've got the kind of nervous system that is highly regulated. You know the idea that you're the sum of the five people you hang out with the most? I like this idea that you're the average of the five nervous systems that you hang out with. Which means it’s important to pay attention to how regulated the people you spend the most time with are. That’s really important.

What are the top three things all of us who aren’t dealing with autoimmunity can do to prevent that from becoming our fate?

Number one, know your ACE score.

Number two, measure the level of inflammation in your body. Inflammation can become elevated seven to 14 years before you develop an autoimmune disease. A good place for basic testing is to ask for a high-sensitivity C reactive protein test.

The fact that 30 percent of people in Dr. Hymen’s laboratory test are testing positive for anti-nuclear antibodies—to me, that's an indicator that the earlier you catch this, the better. The ship could be heading toward the iceberg, and you don’t know it. That was true for me.

My hope is that even if someone doesn’t have an autoimmune disease, they will realize the culture we live in is conspired to create a greater risk of autoimmunity. And this is especially true for women.

What is the No. 1 thing you want all people who’ve been diagnosed with an autoimmune disease to do to try to improve symptoms?

So many people who are diagnosed with autoimmune diseases are told by their doctors, “There's nothing that can be done.” Or, “Why don't you go on a steroid, or a biologic?” Or, they recommend taking a sit-and-watch approach. But the truth is you can do so much when it comes to lifestyle factors. If lifestyle factors are what triggered you into autoimmunity, then lifestyle factors can also help get you into remission.

The way that you eat, move, think, feel, connect to other people—all of these choices can create healing states of consciousness. There’s evidence that all of those things help to call off the immune system and to get it back into a state of homeostasis.

Sara Szal Gottfried, MD, is the director of precision medicine at the Marcus Institute of Integrative Health at Thomas Jefferson University and a New York Times bestselling author.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.