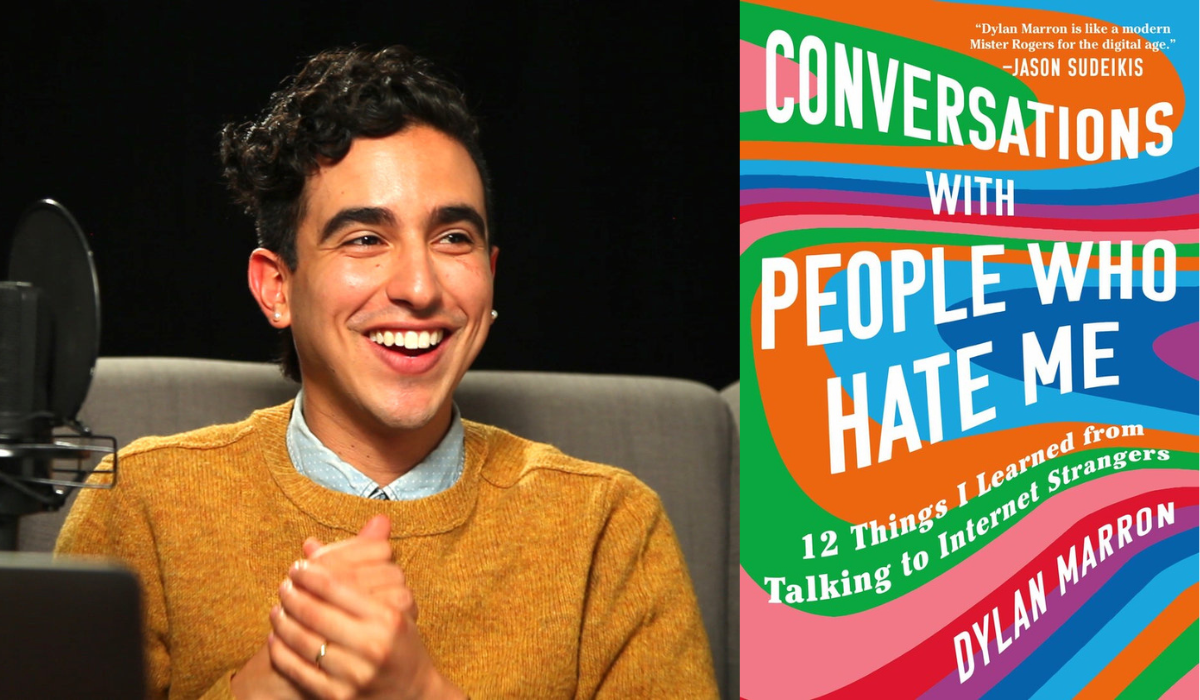

Writer Dylan Marron Reached Out to His Internet ‘Haters.’ What Followed Is an Inspiring Lesson in the Power of Humanity

Dylan Marron has received droves of hateful online messages from strangers. These detractors have commented on Marron’s sexuality, race, talent, and more. Considering this, it might surprise you to learn how Marron—a revered multi-hyphenate video creator, podcaster, and writer—responded. He did not retract. Instead, Marron invited those who wrote him hurtful notes to talk one-on-one.

This social experiment resulted in a podcast, Conversations with People Who Hate Me, and eventually a book of the same name. Marron’s candid, empathetic, and often hilarious recounts of what he’s learned by leaning in with compassion are electric. The Sunday Paper called Marron recently to talk about how our modern digital platforms often further tear us apart and what we can do to inch back together.

A CONVERSATION WITH DYLAN MARRON

You have an innate creativity that you use to explore challenging topics, such as hatred and bigotry. To what do you credit this creativity and curiosity?

I struggle with a chronic sense of not belonging. It's a fear-slash-identity that feels like it looms and permeates so many aspects of my life. When you don't feel like you belong, you become an observer. For me, the only way to make sense of the world has been through a creative lens. That's the truest representation of the way I experience the world, and I feel lucky that I'm able to make work about it.

For years, you've been working on a social project where you reach out to strangers who've sent you hateful messages online and ask them to talk. Every story of connection you share in your resulting podcast and book is enlightening and empathetic, but the story of Josh stands out. You learned after Josh sent you a hateful message that he was bullied in school, just as you were. What did your interaction with Josh teach you?

It's important to point out that my first reaction to Josh was not to be like, 'This is a human. I must empathize with him.' I found security in making fun of his typos. I had the same self-defensive reaction that so many of us have: 'They made fun of me, so I'm going to make fun of them right back.' Especially for someone who was bullied in school, the internet can afford some of us the ability to fight back in a way that we didn't feel we could in grade school or can in the physical realm at all.

Also, to be fair, I would like to be open that I'm not a saint. But the empathic connection [with Josh] happened right away. This practice of empathizing with my detractors was not like this saintly marvel, but this kind of mundane inevitability, and that was certainly true when I talked to them on the phone. The practice of looking through my detractors' online profiles allowed me to create these backstories for them and to learn who they were. Seeing that Josh was this human being who did his high school plays and was raising money for this cause and who had just shared a pic of a recent haircut, I was like, I know this person. I am this person.

Seeing the humanity in Josh's profile helped soften the blow of what he had written to me because it helped contextualize it. It didn't make it less hateful. It didn't make it less homophobic. But it made me feel like this was a person that I could connect with. The fact that I could connect with him allowed me to feel safer in a way that was less like this scary, distant monster contacting me, which is what the word troll evokes, a word I try not to use. Instead, this was a human being who, through a whole host of circumstances, sees the world differently than I do.

You write about bravery and how you believe courage can be expressed in many ways, and not everyone must feel a need to engage with someone who has hurt them. Can you talk about this?

I wrote that in response to the fact that I was being heralded by so many people as a brave unicorn doing this brave thing. Also, I was being labeled, by typically more conservative-minded folk, as the good liberal. And while I very much appreciate the sentiment, I'm an only child, so I live for compliments!—truthfully, I feel really safe to do this stuff. As I said in response to your question at the beginning, I approach all this with curiosity because that feels like the only way to make sense of the world, for me. But not everyone has that response. I want to make sure that while I have found tremendous meaning in the idea of speaking to people who think differently from you and talking to people who have hurt you, I believe doing this always has to be determined by the participant.

I don't want my work to be used as a false example to make others feel like they're not doing this right. Everyone must follow what feels safe and appropriate and what they feel well suited to do.

Your new project, The Redemption of Jar Jar Binks, is a podcast series that digs deep into the character that debuted in Star Wars Episode 1 in 1999. Jar Jar was meant to be a comedic character but ignited many polarizing comments. Why do you feel this story is essential to explore today?

Conversations with People Who Hate Me started with cross-ideological disagreements: Red and Blue discuss topics together. I found tremendous value in that. But the more time I spent doing that project, the more time I spent online, and I became fascinated by and terrified by this uniquely online brand of hate, which was apolitical hate. This is a kind of hate that doesn't appear like hate. The people partaking in it think it is rooted in jokes.

Consequently, this kind of hate doesn't feel like hate on an individual level. When you look at a particle of the swarm of online hate, you may think this is just a harmless joke at this person's or thing's expense. But it becomes hate when you look at the volume of it. And certainly, it feels like hate for the person receiving it.

So I went from being fascinated in mining unacceptable hate, such as homophobia, to exploring more into acceptable hate, like mass jokes at a person's expense. Jar Jar Binks jumped out to me as the quintessential example of this and maybe the first example. Star Wars: Episode One came out right as the internet was flooding American homes. It's not unrelated that this character becomes this huge punching bag because it happens in parallel with the proliferation of internet usage.

Characters have been disliked before in cinema. As an onlooker, I had caught wind that the actor who played this character, Ahmed Best, had suffered with his mental health because of it. I wanted to dig in more to it. I came upon Ahmed Best and found this incredible person who has wrestled with his own story to understand it, more than a victim of such a thing ever should have to understand it. But that's like this cruel truth about our world: The survivors of a thing must become the teachers of how that thing affected them.

I took some time to get in touch with Ahmed to make sure that my intentions were known and that I was not looking to mine past trauma but to present this story as a reflection of ourselves and how we might consider how we partake in this system, too.

We live in divided times, and the gulf between us seems wider because of the internet. What universal thread of hope have you found in doing this work that offers light to us in our mired digital world?

Seeing the world as a collection of profile pictures who will either attack you or at least vehemently disagree with you or make a joke at your expense can make the world feel terrifying. But I have learned, over and over and over again, that one-on-one connection is possible. Not only is one-on-one connection possible, but it can make the world—with social media and the internet that feels like an endless highway of humanity passing us by—smaller and more manageable.

I have also learned that one-on-one conversation makes the inevitable conflict that will arise whenever humans are in any community together, digital or physical, feel surmountable and like a door through which we can walk to better understand ourselves.

Dylan Marron is an award-winning writer and producer. For five years he hosted and produced the podcast Conversations with People Who Hate Me, which gained widespread recognition. Marron’s TED Talk, Empathy is Not Endorsement, has been viewed millions of times worldwide. You can learn more about Marron and his new product The Redemption of Jar Jar Binks, here.