Ever Feel Like Your Body Is Failing You?

Did you like listening to this article? We want to know more about your listening experience.

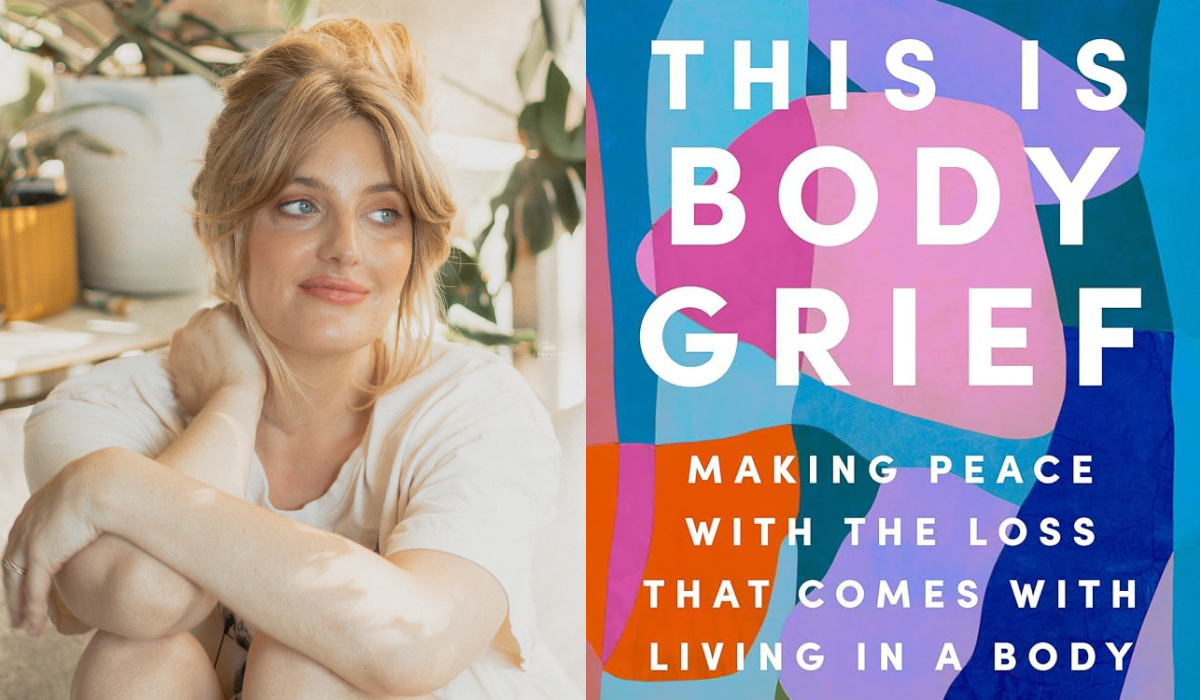

"I was in a significant amount of discomfort. Yet, as usual, I powered through," Jayne Mattingly recalls in her new book. She was 27 and had just experienced an excruciating moment in a workout class that confounded and frustrated her. But she kept going forward—until her body told a different story. Shortly later, Mattingly was diagnosed with intracranial hypertension, a rare neurological disorder. More diagnoses followed, including endometriosis, autoimmune disease, and spinal cord injury, causing her to have 19 surgeries and numerous procedures.

Throughout it all, she wondered, How could this be happening to me?

Mattingly was experiencing body grief, which she says is a mourning and loss around our body when it "changes in ways that seem beyond our control." She powerfully tells of her experience in her new book, This Is Body Grief: Making Peace with the Loss that Comes with Living in a Body, weaving in her story with that of many others, ultimately illustrating how body grief impacts every one of us in ways as diverse and unique as each of us.

But Mattingly's work is anything but grim. With kindness and clarity, she reveals wisdom to help us process the range of emotions that come with the wavering abilities of our bodies. And she shows us, both in her book and below, that no matter how our bodies function, look, or are perceived, "they are always on our side."

A CONVERSATION WITH JAYNE MATTINGLY

To start off, tell us: What is body grief?

It is a universal concept of living in a body and grieving the lives we were once told we could live, the lives we thought we were allowed to live, or the past selves we were holding on to. As a framework, body grief is making peace with the loss that comes with living in a body. That is a simplistic way of saying that living in a body is inherently having grief. It's a heavy burden to be in a body, and the more marginalized we are, the heavier the burden.

Why is it important to understand society's marginalizations and the larger societal context that plays into body grief?

To heal our body grief, we need to understand the isms. You need to understand privilege and the hierarchical structures of the systems that we are taught and put into politically—because our bodies are political, inherently, in this world. So, if we understand the external and internalized isms—sexism, racism, ableism, ageism—and how we internalize those things, we can understand how we're put into this system, how we exist in this world, and how we grieve in this world.

As I started to study the concept of body grief—which is something we've all experienced our whole lives, I just put this name to it—I realized I was writing about systems of oppression. If we took these systems of oppression away, body grief wouldn't be nearly as heavy. If anything, it probably would be irrelevant. Let's put ableism into play. As a disabled person, if I were able to have access to things, if there weren't any barriers for me, if people didn't look down on people with physical disabilities, if it didn't cost $30,000 to get a wheelchair, and I didn't need to advocate for a ramp to just get into a public restroom, then I probably wouldn't nearly have as much grief.

I started realizing that if we took all of that away, how much grief would we really be living with? But we don't live in a world like that. So, we must understand the world we do live in, how we absorb those isms, and how we can live in this world and embrace more body kindness. And how do we do that? Through storytelling, affirmations, journal prompts, and real-life coping.

It is hard enough to have body grief, but even harder to have it in a society that is judging who we are, what we're experiencing, and how we cope.

Yes. And telling us we can't feel our feelings or that we have to feel our feelings in a certain way. If only we all could just feel it, name it, and grieve it without judgment! Whether it's because of injury, disability, aging, menopause, puberty, substance use, eating disorder, or body image, we're all feeling it. But what happens is we then feel it with anger, frustration, and resentment. That is why I break down the natural phases of body grief, to hopefully help people get through a bit easier and with some more grace and compassion.

One of the phases of body grief is the fight phase, which means 'If I fight hard enough, my body will go back to the way things once were.' But you say there's a big cost to this. What is that cost?

Fight is one of those phrases for me that I go back to constantly. I'm really close with my parents, and how they raised us three girls was so intentional and amazing. The way in which my dad instilled hard work in us was beautiful, but it went the wrong way for me. This is not to say it was his fault; it wasn't. But I picked up on this capitalist hustle and grind, your productivity is your worth mindset. And I started to think that if I wasn't always doing, I wasn't worthy. So, throughout my illness, whether I was going through surgery number one, spinal tap number seven, my total hysterectomy, or brain and spinal surgery number 19, I was constantly going back to this fight phase where I felt I was not good or worthy unless I was fighting or working so hard. And I was fighting with my body grief. I knew it was there, but I said, 'I don't care; I don't have time for that.'

A lot of people, especially Americans, do that. They say they don't have time for their body grief. I've talked to so many people in my practice or in my DMs who have said things like, 'I'm in my twenties, and I don't have time for a dislocated shoulder,' or 'I'm in my forties, and I don't have time to go through perimenopause,' and they'll just move forward. But when we disconnect from our mind-body-spirit, the body will stop, whether you want it to or not. The way we will do everything we can to not feel what's actually happening in our body is shocking, and there is a cost.

I would argue that it is never good to push through your pain or push through your grief. Granted, it might be resourceful at the time. I never want someone to look back at their journey and think, I shouldn't have done that. That's not compassionate. But I hope someone can say, 'That was resourceful of me, I have compassion, but now I know more and I want to grieve differently this time.'

You say that being with our body grief is how we heal. What is a step toward healing we can take today?

No matter what our body grief is, we often say, 'Why is this happening?' Instead, I encourage people to lean in and ask, 'What now? What do I need right now?' This is one of the simplest places to start. And it's a nice practice for compassion because it's in the moment. It's not chasing fault. It's not chasing blame.

Let's say you've been feeling really fatigued. This may be something you want to address with your doctor. So, make a doctor's appointment. But if the doctor can't see you for a week or longer, I want you to put it in your calendar and then ask yourself, 'What do I need right now?' Maybe you need better sleep, more electrolytes, some outdoor time, and sunlight. I want you to water yourself, nourish yourself, and give yourself what your body needs right now. And I want you to be compassionate because you can't hate your body into something you think you'll love. Compassion will water into something you will eventually appreciate and be kind to.

How can we each make a difference on a larger scale and spread healing throughout our communities?

Community is the antidote to body grief. The more we communicate and the less we assume, the better. We are all so different. We are all so unique in our stories, but we are all so the same in that we're all human and grieve. Also, what makes us unique is that we all have so many different stories, so if we can stop assuming and ask each other what we need and pull up a seat or a wheelchair to the table and expand the table, that's all we need to do.

Jayne Mattingly is a disability advocate and eating disorder recovery coach. She is the CEO of Recovery Love and Care and the founder of the nonprofit The AND Initiative dedicated to empowering people with chronic illness and physical disabilities. Learn more at jaynemattingly.com.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.