Why Is Listening to Each Other So Hard?

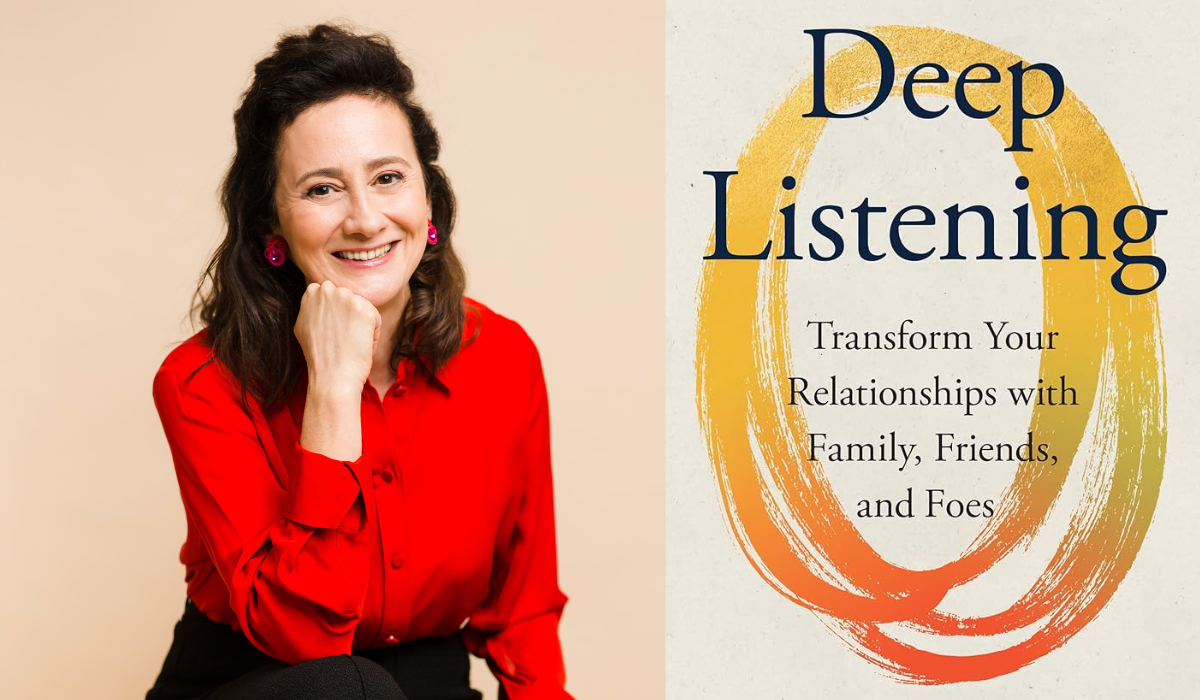

In our ever polarized and distracted world, how can we mend our divides? Emily Kasriel believes we must reinvest our energy in what truly connects us: listening. But not with the transactional type of listening where we look to the other as a resource or a means of information, ready to interject with our own words. What we need is Deep Listening, a way to engage more meaningfully and acknowledge a speaker's humanity, says the longtime BBC journalist, mediator, executive coach, and author of the book Deep Listening.

Over a video call from the UK, Kasriel offered us her guidance on how we all can begin to open ourselves to this expansive, respectful, and encouraging way of communicating. She underscores that Deep Listening is "for conversations that really matter," such as when you disagree with someone, have a relationship to repair, face differing power relations, or come from different backgrounds.

"Those are all really key times when it's really important to deeply listen," says Kasriel. "If people can do that, we can really help the twin crises of polarization and loneliness and make a difference to society."

A CONVERSATION WITH EMILY KASRIEL

How do you define Deep Listening?

Often when we listen, we perform the act of listening. We are 're-loading our verbal gun with ammunition,' getting ready to fire, as theologian Jacqueline Bussey wrote[EK2] . We listen long enough to feel we get the gist of the argument, and then we solve whatever the person is trying to tell us, or we try to cheer them up. Deep Listening is much more profound. It's about the whole of you listening to the whole of them. It's about listening to yourself first and then listening to the other person with curiosity. It's about understanding that you don't already know what the person is going to say, even if it's somebody closest to you, like your partner, your kid, or your parent, because we're not the same person we were last year, last week, or even last night. So, being fully present and open to whatever might unfold allows somebody to think new thoughts and to share much more authentically, which then allows you to feel more connected, the other person to understand themselves more fully, and for you to understand them.

That word “connected” is critical, as you write, "we no longer invest time and energy in the very fiber that connects us: listening." Considering that we live in a world where we spend so much time scrolling and watching quick reels, it's serious. What gets in the way of Deep Listening?

There are so many different factors. Our phone is probably the thing that distracts us most—and even if it's off or you have no notifications, you're still putting energy into not looking at it, which is what's distracting you. So, it's best to keep it out of sight, ideally in another room, when you want to listen.

Another thing that gets us in the way, often, especially in America, is when people say, 'I don't have the time.' People feel so stressed by juggling multiple obligations, so they rush from one thing to another.

Another factor is often, when I used to listen to people, I would complete their sentences for them, because I thought I was doing them a favor. I thought I was saving them time and articulating their thoughts far better than they could do. But you can imagine how the other person felt.

And another thing that gets in the way of deeply listening is the feeling of I am in charge—as boss, as parent, as older sibling—and I'm the person who has to have the answers and solutions. We deprive other people of agency when we try to solve their problems. One other factor that gets in the way of listening, both for men and women, is [the feeling that] I must prove I'm a man, especially in the workplace, because traditionally, men did more of the talking and women did more of the listening. So, men and women today don't want to be seen as weak, as passive, or as mute.

How does Deep Listening help the speaker open up?

The research demonstrates that, as a listener, you co-create the speaker's narrative. Depending on how you listen, the speaker will share more. They will talk about motivations more. They will be more coherent because they feel that they're basking in your uninterrupted attention. So, your role as a listener is so critical. I know from all my experience as an executive coach that when I'm able to really focus and be with somebody, they're able to come to whole new understandings of the world and themselves. And that is so exciting as a listener, when you can see that, and it really helps you stop interrupting—or at least it helped me.

You have created a method that includes steps to help people transform their communication. The first step is to create a space of safety. Will you take us through this?

We need to feel safe. If, for example, you want to talk with a colleague in an open-plan office, they're not going to talk honestly, even if there's a glass door separating your conversation from the rest of their colleagues. You need to think about what might feel safe for the person so they can talk authentically and honestly. Otherwise, you're performing a script and you're not having a genuine conversation. So, if you can, find a private space. Or even better, go for a walk together, somewhere in nature. When we feel free and relaxed, our shoulders, heart rate, and blood pressure drop, we're able to be less defensive and more open, and new thoughts can emerge.

It's also the physicality of it. If you're in a noisy cafe with glass or metal, you're straining to hear and not really able to gauge anything beyond a superficial understanding. Or if there are harsh blue-white overhead lights, that's not so good. It's far better to have softer, warmer side lights to make people feel relaxed. For the book, I spent time with Japanese tea ceremony practitioners who've developed a way to make visitors feel truly cherished over hundreds of years.

Step number two is to listen to yourself—and that feels daunting considering how noisy our world is!

There is so much noise. Particularly in a very important conversation where there's a conflict and you're angry with that person, taking the time to listen to yourself first can be so profound in terms of its impact on the conversation. It's about your agenda: What do you really want to get out of this encounter? Perhaps your relationship is even more important than the quick win that you thought was more important. And then it's also about understanding whether you are projecting onto the other person—stuff you don't like about yourself, your own shadows, or even difficult relationships you had, perhaps as a child. Because in that case, you're not listening to your boss, you're listening to your bullying older brother. And when you're in that encounter, you're not 40, you are 8. And when you're in that defensive, childish, angry mode, how well are you going to provide a place for them to feel heard? So, if we can instead cultivate some awareness—and I would say that if you've experienced trauma, you might need to seek professional help to do this internal listening. This unpacking and listening to yourself is a journey of a lifetime. But beginning to understand what might be triggering us in a particular type of encounter or with a particular individual can be so helpful.

Emily, for the person who may feel triggered, or, as you say, whose inner child is getting in the way, and the mere idea of shifting how they communicate seems hard, what is one thing they can do this week to ease into deeply listening?

There are two things: If you're talking about somebody who's feeling really hard done by and overwhelmed, it's about taking the time to listen to themselves. First, go for a walk in nature. Have a chat with yourself. Ask yourself what's really upsetting you. And let that frightened, younger, 8-year-old self speak. Don't clamp down. Be compassionate towards that 8-year-old because that 8-year-old needs a voice, and if it's not heard, it will come up in every conversation. So, taking the time to be compassionate and understand yourself can be the most critical.

Aside from that and getting rid of your phone during important conversations, it is about being curious. Understanding that you don't already understand, especially if you disagree. Listen up for what surprises you and see what happens. The good thing is that when people feel heard, they dial down their attitude extremity. We did a big project that was just published in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology, and it demonstrated that people practicing Deep Listening not only felt more connected and understood, but also felt more able to reexamine their own attitudes. So, that's a real incentive to deeply listen to someone else because they're going to be more in a position to listen to you.

You can learn more about Emily Kasriel here.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.