How Do You Know What You Truly Want?

It's the most straightforward question yet the hardest to answer: What do I really want? Cultural storytelling, familial expectations, and the fear of being too much subconsciously cloud our ability to open our hearts to ourselves and express our desires. But what if there were a way to break free and claim what we yearn for?

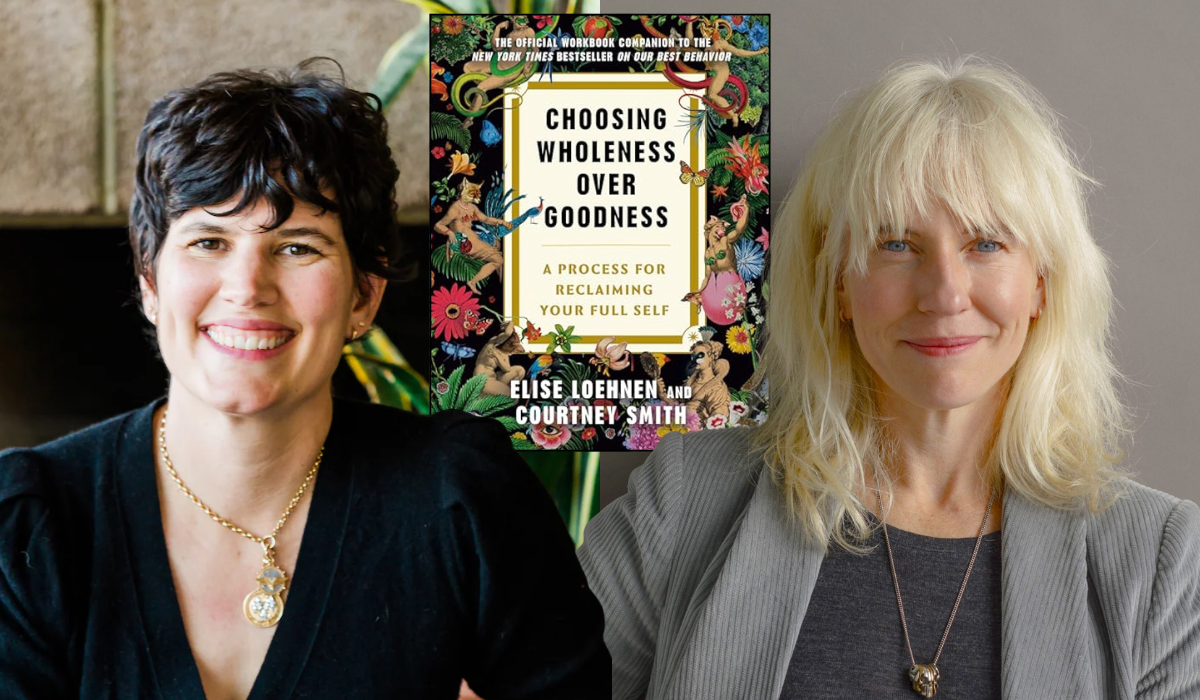

These are some of the possibilities explored by Elise Loehnen and Courtney Smith in their new workbook, Choosing Wholeness Over Goodness: A Process for Reclaiming Your Full Self. The co-authors—Loehnen, a bestselling author, and Smith, an Enneagram expert and coach—cast light on the cultural programming that keeps women disempowered (the crux of Loehnen's wildly bestselling book, On Our Best Behavior), and offer tools to help us reconnect with our inner fire.

Whether you answer the question What do I really want? with gusto or trepidation, Loehnen and Smith's insight offers a compass toward revealing more you in your life. And their work proves that our desires deserve all our attention. As Smith says, “The naming of what we truly long for is the first act in us stepping into our full capacity as creators and agents in our own lives.”

A CONVERSATION WITH ELISE LOEHNEN AND COURTNEY SMITH

Elise, You write that "many of us are uncomfortable asserting our desires in a straightforward way." How have you witnessed this in your work?

Women are conditioned to subjugate what we want to other peoples' needs—women who buck this are perceived as selfish, cold, self-interested, etc. Being called "selfless" is a compliment in our culture, though I can't think of a time when I've heard it applied to a man as it's not something that we expect from them, at all. According to the research of the Incredible psychologist and professor Carol Gilligan, boys (and men) see themselves as being "in" the world, while girls (and women) see themselves as being in service to the world. This is a beautiful idea, sure, I believe we should all be in service to the world—so long as it's a burden that's shared.

Meanwhile, because women orient around serving other peoples' needs rather than our own wants, very few of us can accurately say what we want. I do an exercise with women around wanting whenever I get a chance, and it is very hard for women to give voice to their deepest desires—mostly because they don't even know what their deepest desires actually are. They haven't even thought about it, much less used it as an internal GPS for orienting their lives. What I hear most frequently is triangulation: Women will tell me what they want for other people instead. "I want my kids to be happy." "I want my husband's career to become more fulfilling." And so on.

But when we start working on wanting—both locating the impulse and then naming it—it gets very emotional very fast. For one, there's typically a lot of shame and embarrassment. Who am I to want this thing? It's also closely tailed by feelings of scarcity: If I get what I want, it means someone else won't get what they want. It's really important to stay with the anxiety and even fear that this invokes and then attempt to push a little deeper. Because here's the thing: What women want is beautiful and singular and we'd all be served by seeing those desires come to fruition in the world.

Courtney, You write that many of us suppress or "right size" our desires. What is underneath this?

Courtney: When we dare to articulate our wants and desires, many of us bump up against unspoken stories and fears. For example, many of us are afraid to name what we really, really want because we’re afraid we may not get it, and then we have to bear the pain of failure and disappointment. Many of us are worried that we come across as selfish or self-absorbed, or uncaring about others if we voice our wants and desires. Many of us are afraid that we might sound overly ambitious, overly self-confident, or “too big for our britches” if we speak out loud what we’re most longing for. And many of us are afraid that our wants and desires are in conflict with those we care about and that voicing what we want risks losing relationships.

Because many of these fears remain unconscious and unexamined, one way that we manage them is by “rightsizing” our wants and desires. In other words, we subconsciously limit how big we dream so as to not experience the fears that may arise if we were to really go for what we want. Over time, many women condition themselves to want and dream “appropriately” so as to not experience and face their often fears. We end up living lives that stay safe, but we end up sacrificing contact with what we truly long for and we end up sacrificing knowing what it feels like to live in our full aliveness and full power of creatorship. Rather than consciously being with the pain of the sacrifice we make because of fear, we end up “rightsizing” or keeping our wants small to stay unconscious to just how much we’re giving up.

Elise, in On Our Best Behavior, you write about the hidden messages often hiding in our envy. How can envy be a compass that guides us to what we want?

Elise: In Maybe You Should Talk to Someone, psychotherapist Lori Gottlieb makes a small aside: She tells her clients to pay attention to their envy because it shows them what they want. I couldn't stop thinking about this for months, for two reasons. First, I had a visceral reaction to the word envy: Envy? Who me? NEVER, I would never envy anyone. I've done enough work on myself to know that this reaction meant there was some big stuff to unpack there. I felt polarized against the idea that I could possibly envy anyone. And secondly, I couldn't tell you what I wanted, which made me feel very, very sad.

I see a Jungian therapist and I'm very interested in Carl Jung's theories and so I knew enough about shadow at the time to realize that envy and wanting were creating a shadow-projection cycle for all of us—a cycle that for women in particular just might be at the source of most women-on-women hate. My theory is that we see someone who has something, or is doing something that we want for ourselves. It triggers our envy, but because envy is not conscious for us and completely disowned, we don't recognize that it's present. Instead, we just feel bad and uncomfortable. And we blame the woman who is inspiring our envy for making us feel bad and uncomfortable. Rather than attending to what's happening in us, we look to judge, castigate, deprecate, dethrone, or destroy her: She's bad for making us feel bad. But, if you recognize that she has something you want and it's inspiring your envy you can catch the cycle and use it as a way to figure out what you want: Lacy Phillips calls these figures "expanders." If you flip the frame, you start to understand not only what you want, but what's possible for you. Instead of, Ugh, I don't like her, she rubs me the wrong way, why do people like her books so much, it becomes I want to write a book too, and I want my book to resonate in the same way, and I'm going to study her and learn from her because if she is doing this I can definitely do it too.

In my experience, envy is the fastest and most expedient way to connect with what you want and to start to realize that desire in the world.

Courtney, have a "make yourself blush" practice. Will you walk us through?

Courtney: The “wanting until you make yourself blush” practice is something I first learned from my good friend and teacher Diana Chapman. Because many of us, over time, have learned to keep our wants and desires small, we need a practice where we dream at a level that makes us slightly uncomfortable. “Wanting until you blush” is a sign that you’re wanting to the point that you’ve edged up against the fears that keep you from really standing and going for what your deepest self longs for. Because cultural beliefs about how big women’s wants “should” be unconsciously cause us to dream small, we often need to say what we want out loud, and then we need a push to exaggerate the desire and make it bigger and bigger. The ultimate goal of the “make yourself blush” practice is to keep expanding your desire until it is congruent with what the deepest parts of yourself long to express. This practice is especially powerful when you do it with others because, when we dare to name our biggest wants and desires out loud, we learn that our fear about what might happen, that others will judge or disconnect from us, is often unfounded. Wanting until you blush becomes an invitation to others to support us and it is also a powerful signal to others to dream big as well.

What are some of the questions we can ask to make ourselves blush?

Courtney: Here are some of the questions I use with myself and my clients to encourage wanting at the “blushing level”:

If I made this want twice as big as I just articulated, what would that look like?

If I did not have to worry about what anyone thought or said about me, what desire of mine would I dare to voice out loud?

If I did not have to worry about failing or falling short of what I long for, what would I really go for?

If I closed my eyes and channeled my eight-year-old self and how she wanted with no story about what is possible or what it would take, what would I wish for?

What is an “impossible” wish of mine that is so secret that I have never said it out loud to anyone?

How does daring to say what we truly want expand our lives?

Elise: I really think that any effort to become more conscious and more self-aware about what we're up to is an act of self-healing that extends to the wider world. I also believe that it becomes much easier to get on-side with each other and support each other when we can own our wanting with a solid grasp and go after it directly and clearly. Men are a lot better at this—they've been conditioned to pursue power and go after what they want and because of this, they have a much cleaner relationship with their ambitions and their gifts. Because we're not always conscious of what we want, we often use covert means to get it: We might use people transactionally while pretending to pursue a friendship or manipulate situations so that we don't have to state what we want directly. It's all very human. But we'd save a lot of energy if we could clean all of this up.

Courtney: When we dare to say what we want, we are taking a stand, not that we’re going to get what we want, but that our wants matter. Each moment stands as a precipice with the potential for something new to come forward. What we imagine, what we believe is possible, and, most importantly, what we dare to voice out loud are the ingredients from which this future, our future, comes into being. When we dare to articulate what we want, we claim for ourselves our ability to create and shape the world we live in. We may not get exactly what we want, but the naming of what we truly long for is the first act in us stepping into our full capacity as creators and agents in our own lives.

Elise Loehnen is a writer and editor. She hosts Pulling the Thread, writes a weekly newsletter, and is the author of the New York Times bestselling book, On Our Best Behavior: The Seven Deadly Sins and the Price Women Pay to be Good and the co-author of True and False Magic: A Tools Workbook with Phil Stutz. You can learn more at eliseloehnen.com.

Courtney Smith worked as a management consultant at McKinsey & Co. after earning a JD from Yale Law School. She now offers coaching, facilitating, and consulting services informed by practices she encountered in her journey of self-development, including a masterful understanding of the Enneagram. You can learn more at courtneysmithconsulting.com and read her newsletter here.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.