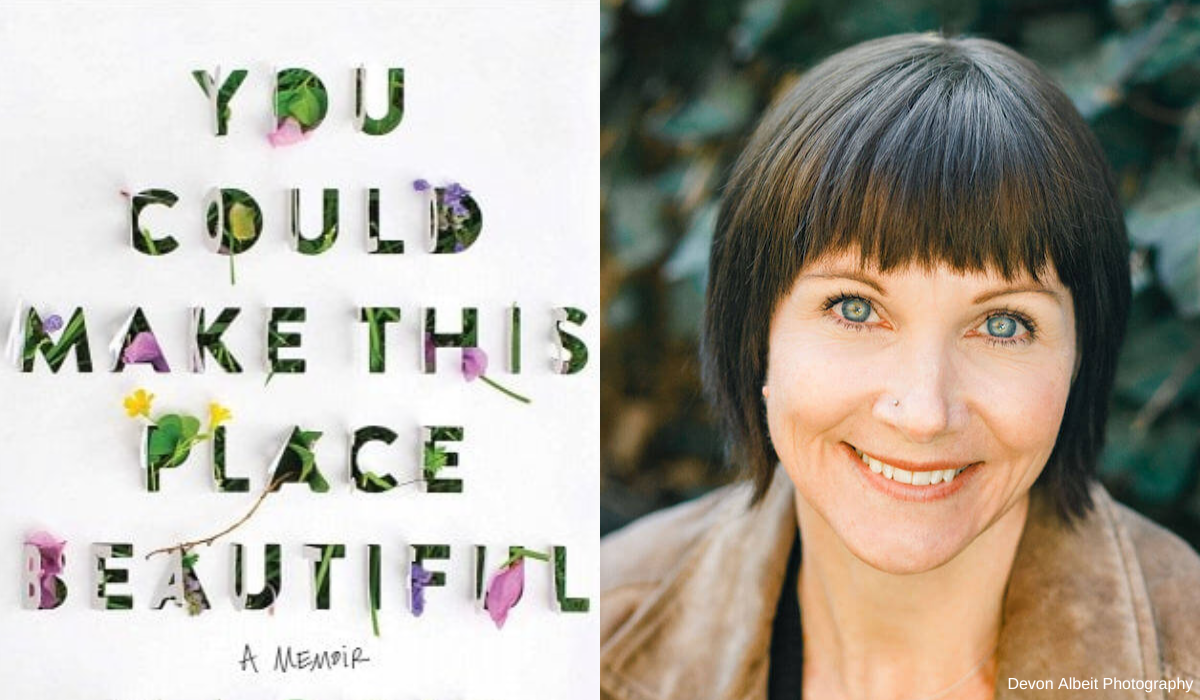

Bestselling Poet Maggie Smith's Divorce Devastated Her—But What She Found on the Other Side Was Exhilarating

If you’re familiar with Maggie Smith’s work, you know the feeling. Your eyes will take in one of her poems, even just a verse, and suddenly you’ll feel an ocean wave swell inside your chest.

Smith, an award-winning poet and writer, tells stories about life’s beauty and pain with such poignancy and depth it opens a new way of understanding our emotions. Her words make you feel less alone.

These are the reasons we couldn’t wait to get our hands on Smith’s new book, her first memoir You Could Make This Place Beautiful. (The title is a final line from her critically acclaimed poem Good Bones.) Using language and cadence that conjures a telescopic clarity, the memoir tells of Smith’s grappling with the end of her marriage and the subsequent piercing to her identity and future. The topic is grave. Yet at its core, it’s hopeful.

Because this is what has come to be expected of Smith, with whom we spoke this past week: She lights a torch to help you see vulnerabilities and strengths—and to know, even in the face of life’s hardships, you are capable and beautiful.

A CONVERSATION WITH MAGGIE SMITH

When a marriage or relationship ends, we tend to forget that the future we envisioned with that person ends, too. You touched on this beautifully in your book: of losing your sense of the future, as you put it. What do we overlook?

The grief of divorce is ambiguous grief because it's not a death loss. It's this strange thing where the person is still in the world, but no longer in the way they had been in your world. And you must navigate that. What we don't talk about enough, particularly with divorce and relationships ending, is the identity hit that you take. Because it’s not just the cognitive dissonance of okay, so maybe this wasn't what I thought it was. It's also a loss that sort of touches everything because your present is remarkably different. Suddenly you are not in that relationship anymore, so that has irrevocably changed. But also, the past is not outside of that ripple effect. When a relationship ends, it's hard not to let that then touch previous memories. Even the good memories may be bittersweet or come with questions.

And then losing the narrative and losing your sense of the future— that for me is one of the most devastating and exhilarating parts of getting to start over. I say getting to because having to depresses me. So I’ve been trying to reframe this for myself. I've been doing this since writing Keep Moving, which is figuring out how to build a life on my own, going forward. It is an independent study, in many ways now, and not a group project. Although I'm certainly not doing it alone—I'm doing it with the grace and love of my kids and my friends and my family and my entire village, thank goodness. But it's very different from what I thought it might be. It’s a lot of recalibrating.

So I don’t think we talk enough about that: You don’t just lose the person, you don't just lose the relationship, you also lose the sense of yourself—and your future.

You write, “I could talk about what a complete mindf*%k is to lose the shelter of your marriage, but also how expansive the view is without that shelter, how big the sky is—.“ What did your marriage ending and reclaiming your identity teach you about yourself and hope?

It was huge. I think about it now and one of the things that pains me is thinking about some of the choices I made as a young person, before my marriage and early in my marriage. All the ways that I didn't honor myself. I try to take responsibility and not point fingers in my book because relationships and families are co-created. I really wanted to figure out who I was, and also how to get back to the best version of myself through the grief of this.

I will say, as I do in the book, that some of the hardest things in my marriage are actually some of the best things in my life. My writing is one of them. Being able to unapologetically lean into my work and honor that part of myself without asking permission or apologizing for it has been powerful.

That agency speaks to your poem ‘Bride,’ which you include in the book. It's quite powerful.

I’m so glad. I love the idea of the sort of Valentine to the self, which is what Bride, as a poem, is. It’s a love poem to the self.

Lastly, let’s talk about forgiveness, a raw topic in your book and in life. You write, “I want to have let go, to have wrestled myself free of this ghost, to have forgiven.” How do you feel about forgiveness after going through this journey?

I've been thinking a lot about the difference between forgiveness and acceptance. Many people I’m close to are practicing Buddhists, and they provide needed perspective. I've been talking to these friends about the difference between forgiveness and acceptance, and I've landed in a place where I can accept, but I don't necessarily need to forgive. I still think that forgiveness is something you give to someone who has offered something to you that says they are sorry. Maybe they say, ‘I'm sorry, I had no idea that that would hurt you,’ or ‘I’m sorry about that text, the tone was wrong, I was having a hard day.’ And then maybe you say, ‘I forgive you.’ But if an apology isn't offered, either verbally or in action, forgiveness feels somewhat inappropriate. And acceptance feels appropriate. This is about having boundaries and choosing the role that person plays in my life. I can choose to let go and set it down.

That's where I'm at now—but I'm a work in progress. I might have a different feeling about forgiveness in six months. But I find that acceptance carries enough peace inside it that gives me what I need, which is not doing the work of carrying around anger or being carried around inside of anger. Carrying a grudge is a heavy weight. I knew that was something I wanted to work through in writing the book, which I have done. It’s not something I’m carrying around, thank goodness.

Maggie Smith is the author of the national bestsellers Goldenrod and Keep Moving: Notes on Loss, Creativity, and Change, as well as Good Bones; The Well Speaks of Its Own Poison; and Lamp of the Body. Her memoir, You Could Make This Place Beautiful, was released on April 11, 2023, which you can order here. You can learn more at maggiesmithpoet.com.

Question from the Editor: Have your experienced losing a sense of your future and yourself? And if so, what helped you forward? We invite you to share in the comments below.