Andrew Smithwick Served Our Country and Now He Is Homeless. This Veterans Day, His Father Is Speaking Up for All Those Who Have Served

What does Veterans Day mean to me and the thousands of other parents missing their sons and daughters? What does it mean to me, the father of a homeless veteran, that the country honors those who have served in our armed forces, those who have fought in our wars and survived, those who fought in our wars and died in our wars?

Families on Veterans Day gather around the photographs of relatives who have served. They watch and listen to Veterans Day stories, patriotic, high-flying, choking-up, flag-fluttering, red-white-and-blue stories on every media outlet.

This wave of sentiment washes over our disunited states, and for one weekend, we are The United States. No red states. No blue states. Rather, a solid monolith. The wave of solidarity lifting and carrying “our boys” to the forefront of our attention hits its peak at 11:00 a.m. on Saturday, November 11—marking the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918 being the moment universally acknowledged and celebrated as the end of World War I.

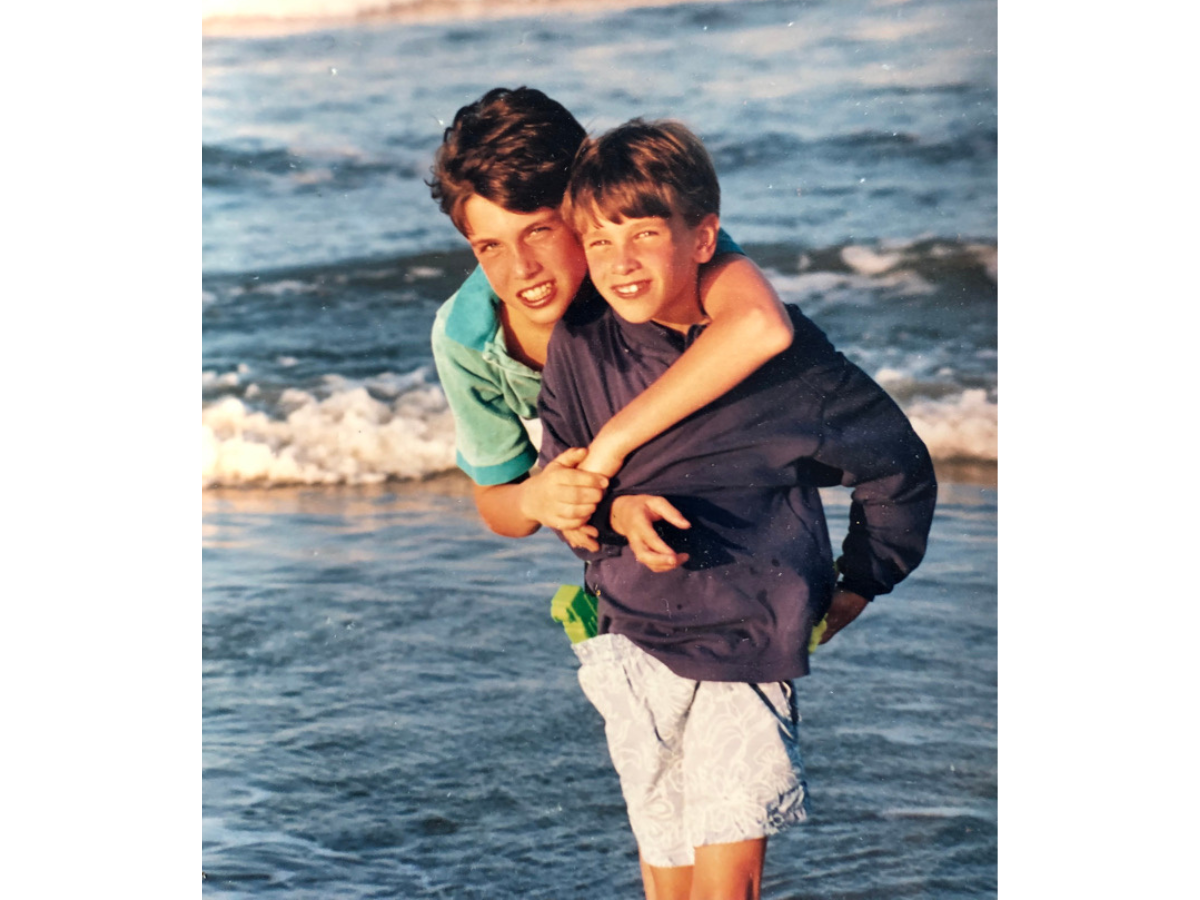

For so many of us, Veterans Day is a milepost on our ongoing odyssey of experiencing the ambiguous loss of a loved one. That loved one progressed through infancy, childhood, and adolescence, then often, almost immediately, entered the military at the age of 18, 19, or 20.

They went off to war young and idealistic, upbeat, strong, and razor-fit from their training, then returned home damaged with no present, no future. These are the homeless veterans with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Most of these homeless veterans are not begging. My son Andrew does not beg. Most of them are not visible. We’ve been searching for Andrew for six years. He is off the radar of our modern American life of surveillance and computer cookies and video cameras and medical files. He’s cut off from the simplest transactions with state and federal governments through licenses and taxes.

Andrew, along with thousands of other homeless veterans—most of them lost to their families and making no effort to reconnect—will not be celebrating Veterans Day.

How many are out there? On November 3 of 2022, the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) announced results of the 2022 Point-in-Time Count showing an 11 percent decline in veteran homelessness since early 2020. There are 582,000 homeless Americans, and 33,136 of them are veterans. This is far down from the over 70,000 in 2010, before HUD and the VA began making solid progress reducing the number on the streets using the evidence-based “Housing First” approach, and eventually, by 2022, providing over 40,000 homeless veterans with safe housing.

“One Veteran experiencing homelessness will always be one too many, but the 2022 PIT Count shows that we are making real progress in the fight to end Veteran homelessness,” said VA Secretary Denis McDonough.

Although there is progress, there is no end in sight for our search for Andrew, for our one veteran experiencing homelessness. It’s been five years since we last saw Andrew, since I kneeled in front of him outside a hospital where he’d just been released from the psychiatric ward while the police circled us—the lights on their cruisers blinking and flashing, his sister and mother crying—and we told him we wanted to help him, before an officer gently gripped my shoulder and pulled me away.

We push on. Other families push on searching for their one veteran. I recently received an email from a man whose son served multiple tours in Afghanistan and Iraq, and who steadily rose through the ranks. Each time his son came home, he was in worse shape, treated his wife worse, frightened his two children, and lapsed into violence and depression, showing all the signs of PTSD. Finally, he was aptly diagnosed and was immediately decommissioned. (That’s the Catch-22; if you are in the military, seek psychiatric help from the VA, and are diagnosed with a mental disorder—then you must leave your livelihood and way of life which you may have grown to love.) Shortly afterward, he was found dead. This father admitted that the thought had crossed his mind: Would it have been better if his son had died in battle—his body ceremoniously returned home, his service celebrated—instead of going through the long and inexorable descent into depression, schizophrenia, paranoia, which led to mistreatment of his family and outbreaks of violence?

Not one of us in our family wishes that our Andrew Coston Smithwick had been killed in action. Each of us has hope—hope that we will find Andrew and get him help. On Veterans Day, we continue our experience of relentless, grinding away, day-after-day ambiguous loss, a leeching of the soul, versus the without-a-doubt worse experience of a final loss, the final loss: clear cut and absolute death.

We have lost Andrew…. Yet, we have not lost him.

We know he is alive, living as a homeless survivalist, pushing his bicycle loaded down with clothes and camping gear, somewhere in the Southwest. And yet—in reality, at this moment, we only know that he was sighted two months ago—that he was alive and healthy then, on that day.

We carry that image forward, project it on the screens of our minds, for one week, three weeks, five weeks, until it begins to fade and we begin to worry again. What is my son doing? Where is my son sleeping? What is my son eating? What is my son thinking? Does he remember us? Is he in good physical health? When will this end? “Andrew,” I call out during an autumn quick-stepping hike at dusk. I am imagining him. I am channeling him. I am doing a Marine forced march with him. “Andrew, where are you?” I call out, sending my voice into the blood-red sky and across the country to New Mexico where he was last seen. I march lock-step with him. “You can’t keep living this way day after day, year after year, into your forties.” And I think: I’m in my seventies. I have less and less time left to find you, Andrew. I cannot, I will not, end this life with you still out there camping on the banks of rivers and in the foothills outside American cities, pushing your bicycle packed with gear down city streets.

Veterans Day for our family is a vacuum craving to be filled. A black hole in our hearts. Veterans Day, for us, is the bull’s eye of a target that America hits with perfect aim every year: the horror of war, and the hole in our hearts that only the return of Andrew can fill.

We cannot thank Andrew for his service. We cannot sit around the dinner table laughing and joking about good old times with Andrew. We wish he could be here with us: shaved, short hair, out of his homeless mufti and duct-taped go-fasters. Tall, trim, handsome, in his dark, olive green Marine uniform, his jacket perfectly fitted, marksmanship badge on left chest pocket, colorful long narrow ribbon bar above detailing his service to our country: Global War on Terrorism Medal, Iraq Campaign Medal, Sea Service Deployment Ribbon, Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal.

One day, we will have Andrew back. He will not be wearing his uniform; that’s a romantic notion that sounded good for a moment, but drawing attention to his years as a Marine is not Andrew’s style. He is a quiet and modest man.

Andrew! Are you reading this? I can feel my arms wrapping around your steel cage of a chest and joyfully lifting you off the ground.

Andrew, you must realize you can get help and housing from the VA. You can start your life over.

Andrew, the war’s over. Come home.

Patrick Smithwick is the award-winning author of The Racing Trilogy, Flying Change and Racing Time, and his latest book, War's Over, Come Home: A Father's Search for His Son, Two-Tour Marine Veteran of the Iraq War. He and wife Asley live in Monkton, MD and are the parents of Paddy, Eliza, and Andrew.