“How I Learned to Stay With What Once Overwhelmed Me”

My husband once said to me—half laughing, half loving—“Nothing clears a room faster, Sally, than talking about your childhood abuse.”

He wasn’t wrong.

If I’m giving a talk, or speaking to friends or any group really, and I say something like, “I had Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) and it developed as a result of the childhood sexual abuse by my mother and father,” there’s often at least one person who turns away, shifts in their seat, looks down, closes their eyes, crosses their arms. Sometimes more than one person. Sometimes the whole group.The air shifts.

And there it is. That’s dissociation. Theirs—not mine.

It’s normal dissociation—a way the brain protects us from overwhelming information or feelings that are too much to process. This kind of dissociation, even for people without trauma histories, can happen as a temporary way the mind differentiates overwhelming experience from conscious awareness until it can be safely integrated. Our brains protect us long before we even know we need protecting.

Similarly, as with DID, you might feel numb, detached, foggy—as if you’re floating outside yourself. Or like what you’re seeing or hearing isn’t real. But unlike with DID, it’s temporary. It doesn’t cause memory gaps for large swaths of experience. It doesn’t create dissociated states of mind or protective memory barriers between them. It’s often just part of the human experience. It’s all about protection. The mind’s first job is to protect. Its second is to heal.

So, here’s the thing: If simply hearing a story like mine causes such a reaction, imagine what it’s like to live inside it—as a very young child—for a long time. I was a child. There was no way out. The people hurting me weren’t strangers, they were my parents. The people I depended on to care for me. My system couldn’t integrate what I was experiencing. When our attachment circuitry for safety and connection tell us to go toward our parent for safety, but our parent is the danger, a child can’t make sense of it. So the brain does the one thing it can to protect you: it fragments.

That’s how DID can develop. It’s not crazy. It’s not split personalities. It’s not psychotic or sociopathic. It’s not a personality disorder. And it’s certainly not a joke or how Hollywood has portrayed it for years. It’s the brain performing mental gymnastics to survive the impossible. In fact, it’s a brilliant adaptation.

When I began therapy at age thirty-seven, I didn’t know any of this. All I knew was I felt like I was losing my mind. Terror. Dread. Visceral responses that made no sense to me. Emotions and sensations that didn’t fit my life. Memory gaps. And not a single memory of my childhood.

In therapy, Dr. Dan Siegel listened, followed, and attuned to me. He created a sense of safety I’d never before known. After a few months, he gently told me what he thought was happening. I had something known as Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD), which is what DID was called back in 1991.

“Then I’m crazy after all,” I said.“No, Sally… you’re just the opposite of crazy,” Dr. Siegel replied.

His words that day set the tone for everything that followed. Just the opposite of crazy. My mind—my very young mind—knew what to do. It fragmented. It dissociated. He knew then what I’ve come to know now, which is that my abusive family was the problem, and my dissociation was the solution. It saved me.

And Dr. Siegel’s words, which I can still hear today, nearly a third of a century later, let me know there was hope. That he never doubted. I can’t really describe the impact that had on my recovery. Its meaning has been immeasurable.

A pivotal point for me in therapy was learning about something called the window of tolerance, which is the range within which we can stay present to our emotions and sensations without becoming overwhelmed or shutting down. When I was a child, terror pushed me far outside that window, and my mind had to fragment to survive. Later, as an adult, I often bounced around that window, sometimes flooded in chaos, sometimes stuck in rigidity. Knowing wasn’t safe, even though knowing was the key to it all. In therapy, I began to widen that window—to stay longer with feelings that once felt unbearable—safely, with Dr. Siegel’s presence guiding me back into connection.

Through the lens of Interpersonal Neurobiology (IPNB), I came to understand integration—that it’s not about getting rid of states of mind but honoring them all and linking them. I could have a state of mind that got me through a night of abuse and terror and wake up the next morning to have breakfast with the terrorizing person and still be able to go to school.

In therapy I came to know all of the dissociated self-states—when and why they came into existence in my innermost world, how they figured out ways to help me, and what life was like for them, helping me know ultimately what life was like for me. I came to honor each self-state and link the experiences they held for me. I moved toward wholeness as each state came to know that their memories, perceptions, and strategies were honored—forever part of the fabric of my being. Not lost or eliminated, but connected to a larger whole. A larger, whole me.

This is what healing and recovery were for me—connection, honoring, linking, years of safe internal reflection, harnessing the power of neuroplasticity to rewire my brain, and the therapeutic bond with Dr. Siegel based on safety and connection. I came to resolve the traumas of my childhood, dissolve the memory barriers of DID, and no longer live a dissociated life.

And so now, when I tell my story and notice how hard it is for some to hear and sit with, I hope people can begin to do just that—notice the discomfort, the instinct to turn away—and stay. Bring curiosity to what they’re feeling. Go toward it instead of away. That’s where the healing is, not just with my story, but with any hard truth life throws your way.

Don’t turn away. Turn toward. That’s where healing begins. Because it’s not about being stoic or toughing it out. It’s about learning how to stay within your own window of tolerance, learning how to feel without getting swallowed, how to know something hard without shutting down. That’s what integration is. That’s what awareness gives us—the ability to stay present and whole, even in the presence of difficulties and pain. And thanks to neuroplasticity, the more we do that, the more our brains wire for it. Awareness becomes capacity. Staying becomes strength. Presence becomes peace.

Because when we can stay with the truth—ours or someone else’s—we don’t just survive it. We transform. When we stay with the truth, the truth sets us free. It’s not about forgetting, it’s about knowing and integrating our experiences—both good and bad—into the whole of our being. The same mind that once protected us can also set us free. That’s the brilliance. That’s the hope.

What once cleared a room now widens it—widens our windows of tolerance—filling the space with presence, courage, and truth.

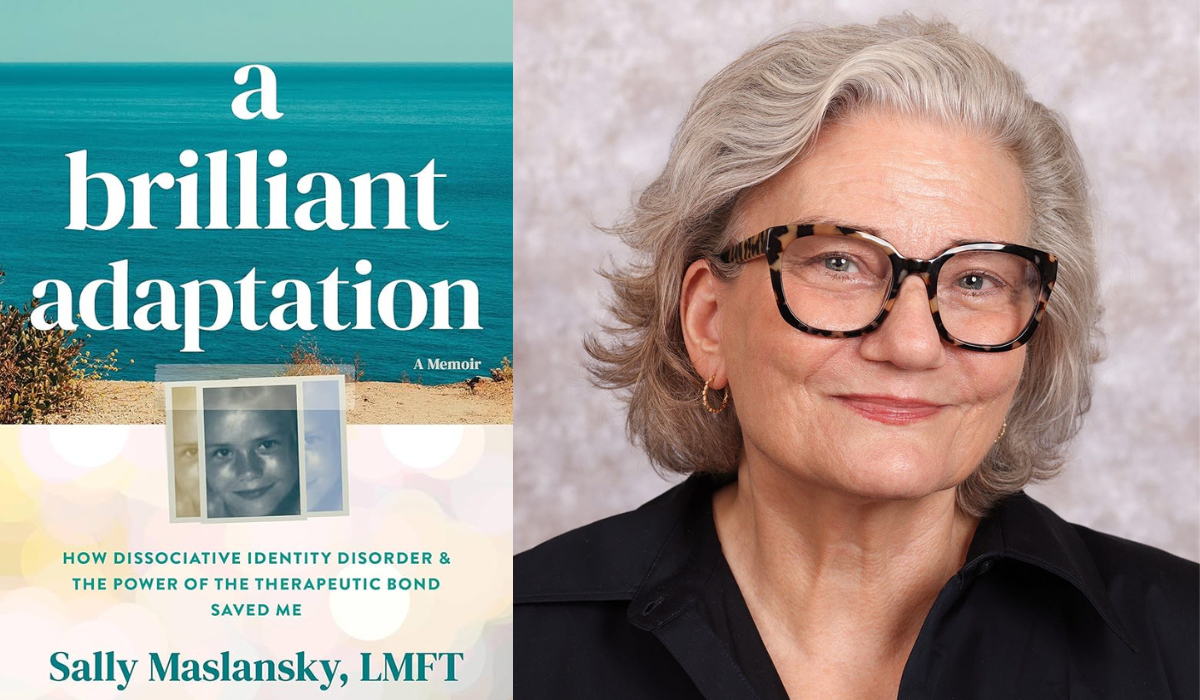

Sally Maslansky is the author of A Brilliant Adaptation: How Dissociative Identity Disorder and the Power of the Therapeutic Bond Saved Me, coming January 2026.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.