The Gift of Feeling Like You Don’t Belong

“When we understand the heart of a stranger and we help others belong, we not only give them a gift, but we actually feel more at home ourselves.”

Rabbi Angela Buchdahl has spent much of her life navigating what it means to belong—and turning what it feels like to be an outsider into a superpower.

As the daughter of a Jewish American father and a Korean Buddhist mother, she grew up straddling cultures and fielding plenty of insensitive comments because she didn’t “look” Jewish. Even on her path to the pulpit, she faced doubt. Would a mixed-race woman ever be seen as authentically Jewish? Could she lead one of the largest, most influential congregations in the world?

Instead of turning away from those uncomfortable feelings of otherness, she embraced them—and it became a great source of empathy and strength. In her new memoir, Heart of a Stranger, Rabbi Buchdahl shares how feeling like an outsider shaped her. This week, we sat down with the rabbi to talk to her about how our own moments of “otherness” might open the door to more compassion, connection, and healing in our lives.

“When we understand the heart of a stranger and we help others belong, we not only give them a gift, but we actually feel more at home ourselves,” Rabbi Buchdahl tells The Sunday Paper.

In a world that feels increasingly divided, Rabbi Buchdahl’s message is more important than ever.

A CONVERSATION WITH ANGELA BUCHDAHL

You grew up as the daughter of a Jewish American father and a Korean Buddhist mother, and you speak candidly about feeling like an outsider. Looking back, how did that outsider status shape your sense of purpose and your calling?

I think that every one of us wants to find home and a sense of belonging. It wasn't always easy for me; I didn't quite fit into any of the groups that I wanted to be a part of, beginning with being biracial in Korea, which was very challenging, then coming to America as an immigrant, and then being in the Jewish community and being Korean.

That being said, I learned early on from my parents that home is wherever your people are. I also knew what it was like to feel like an outsider, and that became the source of my sense of empathy for others who know what it feels like to not belong. It made me a little bit more resilient. It gave me a little more grit, and I had to be a little more creative about how I found my way.

In many ways, I think this has been the story of the Jewish people throughout our history. And so, I also drew some wisdom from some of the stories of our own ancestors who had to do the same.

What might all of us learn from your experience of “strangerhood” when it comes to navigating life these days, in such a fractured world?

It's an era with a lot of identity politics, and we like to put people in boxes and describe people with some kind of categorization. But human beings are complex, and we are usually navigating multiple identities. You don't have to be biracial to feel like you've got a lot of identities. Sometimes it's about where you come from. Sometimes it's related to class, or race, or ideology.

The interesting thing is, when we do carry those multiple identities—and when people want to put us into one box— the fact that that doesn't really fit often means that we feel like we don't belong or we are outside. While I often felt like my experience was unique because there weren't a lot of Korean Jews growing up where I was, I realized that everyone in some context or another feels this way. And if we could actually harness that feeling of knowing what it feels like to have the heart of a stranger as the starting point for our connection with others, it would be deeply important.

In our country, we used to have many communal meeting places—churches, synagogues, bowling clubs, bridge clubs, Elks clubs. People who had very different ideologies and politics and even different races would gather and get to know each other and get to know each others’ stories. Unfortunately, many of those kinds of places have disappeared from our cultural life, institutions, and societies. What we've lost is our ability to get to know people and their stories, especially across lines of difference. I would push us to get to know each other's stories better.

You confront what it means to be “really Jewish” and how you’ve been challenged by some in the community. What have people said to you? How has this impacted you?

I figured out pretty quickly that I didn't look like most of the Jews in my synagogue. Even though I looked different, most people accepted me. But if I went into a new Jewish space, I got comments like, “You don't look Jewish.” Or, “Tell me, how did you become Jewish?” When you walk into a Jewish space and are asked those questions every single time, it's very othering. It's very clear that others are thinking, We can tell that you don't belong here.

In the Jewish community, when people asked me questions like these, they thought it was okay because there was a presumption of how Jews looked, what their last names were, what their nose looked like, or some ridiculous kind of stereotype. And so I had to work past this idea people had of what it means to be Jewish.

In my teens, I was president of my synagogue youth group, and I learned that there's a traditional Jewish legal definition that your identity and status are traced through your mother's line, not your father's. With a Buddhist mother who was not Jewish, suddenly I understood that people did not consider me Jewish at all, and it was deeply painful and in some ways destabilizing. Ultimately, I ended up deciding to have a re-affirmation ceremony, which some would have called a conversion, although I had been Jewish my whole life so I don't know how I could call that converting. It wasn't to prove to others that I was Jewish, because ultimately I knew that for most people it wouldn't change their minds. It was for me—a culmination of some searching, and it gave me a ritual marking.

If there’s one question you hope every reader might ask themselves after finishing Heart of a Stranger, what would it be?

How could our heart of a stranger, our feelings of outsiderness, help us make more belonging for people who deeply need it, and for ourselves?

When my mother was new to this country, felt so much like an outsider. As soon as she had settled in, she helped bring her sisters to this country, and then she became an English as a second language teacher and taught hundreds of children who came here from other countries. She taught them English and helped them integrate into America. She had this desire to bring people in and welcome them. I realized that in many ways, this act of welcoming others is one of the ways that you feel belonging.

When we understand the heart of a stranger and we help others belong, we not only give them a gift, but we actually feel more at home ourselves.

How do you rise above the noise in our current climate of non-stop inputs? Are there practices or prayers you turn to?

I have some spiritual strategies that are ancient. I'll begin first with the Jewish idea of a Sabbath a once a week. It’s an electronic detox, a prohibition of running errands or being productive, and a space to just be. To be with your loved ones, and time to not create, produce, be ambitious, or check your to-do list. A once-a-week Sabbath is absolutely essential to my well-being.

I also find prayer to be a way that I focus my mind, attention, and energy on the important things. Whether it's directing prayers to the people I love or directing prayers to myself, talking to something bigger than myself—I'll call it God, people can call it something else—helps me articulate my deepest desires, needs, and gratitudes.

Also, silence is important to me. We fill our lives with noise. And it’s more than literal noise. We do not let ourselves clear our heads. And when that white noise has no place to be released, it will interfere with our interception of the true messages that we need to hear in our lives.

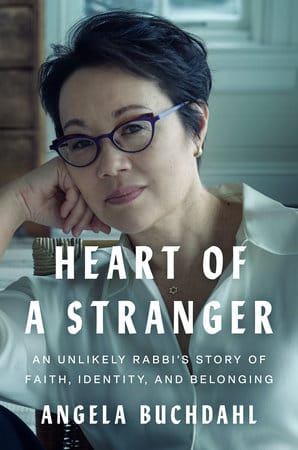

The photo on the book cover may not be how one expects to see a rabbi. What’s the story behind that?

My publisher wanted to make sure that the cover was a picture of me, because I think they wanted to communicate immediately that I was an unlikely Rabbi. I was very fortunate that the illustrious and brilliant photographer, Annie Leibovitz, is a member of my congregation and a friend. She offered to take the book cover for me as a gift, which was really nice.

This is the genius of Annie. She didn't want to just do the photo shoot. She wanted to read the entire book. She not only read the entire thing, but came to the photo shoot with highlighted sections that spoke to her. And so there was something she wanted to capture—what she was feeling in the spirit of the book. And the picture is absolutely unlike any other picture I've taken, not just because of her magic with color and light and all of that, but because I'm not smiling, and I always smile in pictures.

Annie wanted to capture something contemplative and thoughtful. I love it.

Do you think we will ever repair the way people feel about Jewish people and the state of Israel? Or are we beyond that possibility?

I think history has shown us that antisemitism is very durable; it never goes away. It doesn't mean I don't fight it. But we know that this is the world's oldest hatred, and it has unfortunately blossomed more in the last few years. But history has also shown us that this is not a linear line. It can get worse, and it can get better. Oftentimes when a society is more polarized, rising antisemitism is actually the canary in the coal mine for a kind of illness that's spans across society. We should all be fighting antisemitism in the same way we should all be fighting all forms of hate and bigotry.

I am very hopeful that, God willing, now that the last living hostages are back from Israel and that there is a very fragile ceasefire, Israel can be in a better place, and the Palestinian people can be in a safer and better place.

The Jewish people are strong and resilient. I think that one of the things that we will continue to do is build bridges, and I hope, contribute to the communities that we are a part of. And that that our allies and our friends will come to know who we are as we build the country that we want to build together.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.