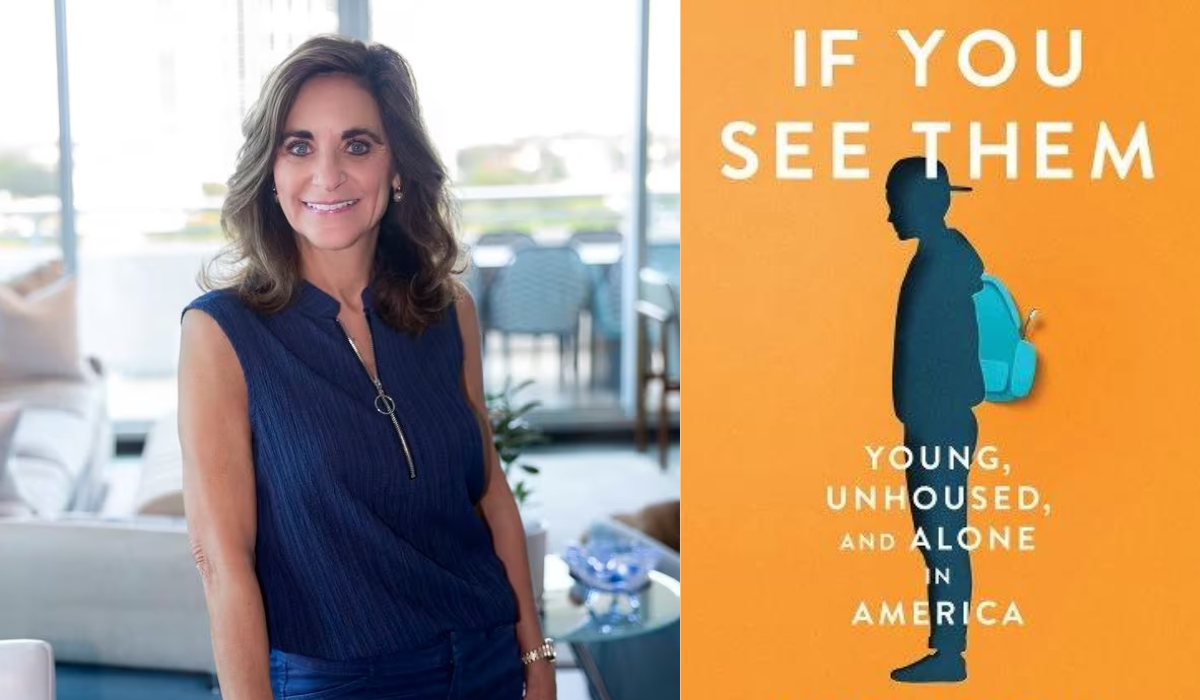

Millions of American Kids Are Homeless. Meet the Woman Fighting for Their Future—and Inspiring Us All to Do the Same

It’s widely known that America is grappling with homelessness. But within this truth is a subset of people Vicki Sokolik says are “forgotten, almost invisible”: all the homeless kids. They live in cars, parks, street corners, and on friends’ couches, surviving in plain sight—and our system is failing them. “We know about ‘runaways,’” Sokolik writes in her book If You See Them: Young, Unhoused, and Alone in America. “But do we know why kids run away—or what they are running from?”

Sokolik began asking these questions two decades ago when she and her family started helping a student who’d escaped an unsafe home and dropped out of school to survive. Little by little, Sokolik helped more kids, offering them a haven in an unforgiving world. As she opened her home and heart, she saw how giant the issue of homeless youths is today. Kids are fleeing for endless reasons, from neglect to racism to poverty to sexual abuse, and they have no safety net. They also have little recognition from the state or general public.

We sat with Sokolik to talk about the nuances of youth homelessness and why this issue needs all our attention. She tells us how her nonprofit, Starting Right, Now, is helping youths and evolving legislation, and how we can all start making a positive difference in the lives of these vibrant, incredible, and overlooked kids.

A CONVERSATION WITH VICKI SOKOLIK

How do we misunderstand the problem of homeless youths?

Before I started doing this, if somebody had told me that a kid left or was kicked out of their home, I would have immediately said, 'The kid's a problem.' But actually, that is so wrong. A child has inherited inequities that they had no control over. If they are homeless and they enter the classroom and haven't slept or eaten, and they're so angry about their situation, they may spew things off to a teacher or put their head down because they don't want to work. And instead of asking what's going on, we blame the child. We say the child is lazy, non-compliant, and doesn't want to do the work. I've never seen a child who did not want to do the work. I've seen a child who could not do the work because of circumstances. You're not focusing on school when you're so worried about where your meal is coming from or where you'll lay your head at night. That's one area that needs to be addressed: Kids do not go into the classroom all the same way. Kids don't just act out. There's a reason.

That touches on another point you bring to light: How society overlooks these children. They lack stability and homes, but they are still in society—in classrooms, on sports teams, and around town.

Correct. Take Courtney [in the book], for example. She was smart. She joined the lacrosse team because she knew that that was where she could shower.

There are estimated to be at least 1.7 million unaccompanied homeless youths in America right now, but you say that is a grave underestimate. How serious is this problem?

It's really serious. Every student I interview [at the non-profit] has not yet been coded [documented]. So, I have to assume the number is at least double, if not more. Also, so many kids hide. They are not coming forward and are instead dropping out of school or ending up incarcerated, trafficked, or dead. They'll often walk down a street and pull car handles until one opens, so they'll sleep there for the night. Survival sex is common. So, that number is inaccurate. It's a major problem, and it is truly an invisible epidemic that, if we do not deal with it, will lead to very unsafe communities.

There's a giant amalgamation of issues, from abuse at home to a lack of food to racism, and those issues are different for every young person. In your two decades working to help these kids, what are some of the significant flaws in policy that are failing them?

In Florida, where I live, I've been very fortunate that they listen now. They understand who these kids are. But honestly, the very first time I went to testify, there was just an assumption that these kids were in foster care. And that's not true; they're not. They're not eligible for foster care because they weren't taken out of their home.

If you do not allow the kids in every state to get their birth certificate and social security card, they can't even work. So now, they're forced to do something illegal to survive.

Another issue is medical care. Before the kids enter our program, they use the ER for medical care, which is costly for the community. When it's a chronic stomach ache because they're not eating well, the doctor is looking at them instead of the person having a heart attack. Secondarily, they need to be able to consent for their health care as minors because who's consenting for them? That's also a problem.

There are other things here that we are working on, and I'm going to battle, but those are significant issues that must be addressed immediately.

You're not a social worker, and you did not set out to do this work; it found you. Tell us more about your journey and what your non-profit, Starting Right, Now, provides.

Initially, we were giving a student a bed and getting them through high school. That was the goal. But what I found was these kids walk in so angry and traumatized, and if all we did was provide them with that, they would get their high school diploma, but they would still leave angry and traumatized. So, we developed a curriculum that helps these kids get rid of shame because shame is one of the biggest inhibitors of moving forward. We want these students to be able to stand up and proudly tell their stories. They're so inspirational.

At SRN, we have them do anger management, mindfulness, boundaries, and meditation classes. They learn etiquette because most of them have never been to a restaurant. We provide intense academic support, and we have an agreement with the school districts that we can do credit recovery in our offices. For the past 16 years, we have graduated every student on time, which I'm proud of. We also have a finance department. The students have to get a job, and with their earned income, they have to open a checking and savings account that we help them manage. They must create a budget, and 30 percent of their income must go into savings. Through our alum survey in 2020, we found that 87 percent of our kids still follow the SRN budget and had more than six months in savings during the height of the pandemic, which is above the national average for anyone their age.

Also, every student is matched with a mentor who touches base with them every day and takes them out once a week to do an activity. We also found through the survey that 90 percent of our kids still talk to their mentors. On top of all that, we have a social services department that helps the kids get food stamps and arranges all their mental health care, medical care, transportation, and anything else to help them holistically.

What is your advice to someone who wants to help but may feel overwhelmed by the problem or under-resourced?

I started this where I was and with what I had. I was helping one student, one family, and through them I was learning. I didn't know anything; I was so naïve. What ends up freezing people is the thought of having to look at the whole picture. You don't have to. Literally, do one thing, one day at a time. And before you know it, you are helping someone. Not everyone has resources to give, but everyone does have themselves. You can read to a kid who has never been read to. If you see a kid sitting in a park, go talk to them and ask if you can bring them to social services. Just one thing. If everyone did one thing, it would be incredible.

That goes back to the title of your book If You See Them.

Yes, they're literally everywhere.

Vicki Sokolik is the founder and CEO of Starting Right, Now (SRN), a pioneering nonprofit that provides social and health services to unhoused students in Florida. A CNN Hero, she has co-authored and amended legislation to pass ten bills protecting unaccompanied youth statewide.

Please note that we may receive affiliate commissions from the sales of linked products.